Probe and Ponder

1. What might you see if the invisible world around you became visible?

Answer: Imagine if we could see the tiny, invisible world of microorganisms with our naked eyes! You’d see a bustling, colorful world full of life all around you—on your hands, in the air, in water, and even in your food! Here’s what you might notice:

- Shapes and Movements: Tiny creatures like bacteria (rod-shaped, spherical, or spiral), amoebas (shapeless blobs that wiggle), and fungi (thread-like or mushroom-like) would be everywhere. Some might be swimming, crawling, or just floating.

- Crowded Places: A drop of pond water would look like a busy city with millions of microorganisms, like paramecium (slipper-shaped) zooming around, eating tiny bits of food.

- On Your Skin: You’d see bacteria living harmlessly on your skin, looking like tiny dots or chains, helping protect you or just hanging out.

- In Food: In curd or bread, you’d see yeast (tiny ovals) making bubbles of gas or bacteria turning milk into tangy curd.

- Colors and Glow: Some microorganisms, like certain algae, might glow or look green, red, or even shiny under light.

It would feel like discovering a secret world, like a jungle or an ocean, but too small to see without a microscope!

2. How might your observation of this hidden world change the way you think about size, complexity, or even what counts as ‘living’?

Answer: Seeing the invisible world would make you think differently about size, complexity, and life itself. Here’s how:

- Size: You’d realize that even the tiniest things, like bacteria (smaller than a grain of sand), can do big jobs, like breaking down waste, making food spoil, or helping plants grow. Size doesn’t decide importance!

- Complexity: Microorganisms may look simple (like a single cell), but they’re super complex. For example, bacteria can “talk” to each other using chemicals, move toward food, or even fight diseases. A single cell can be as busy as a whole factory!

- What Counts as Living: You might wonder if a single-celled amoeba, moving and eating, is as “alive” as a human or plant. Microorganisms grow, reproduce, and respond to their surroundings, so they’re definitely living, even if they’re tiny and don’t have brains or hearts. This might make you rethink life—maybe even a virus (which needs a host to multiply) could seem partly alive!

3. How do these tiny living beings interact with each other?

Answer: Microorganisms don’t live alone—they interact with each other like neighbors in a community! Here’s how they might “talk” or work together in their hidden world:

- Helping Each Other: Some bacteria and fungi team up. For example, in soil, fungi provide nutrients to bacteria, and bacteria help fungi break down food. In your stomach, good bacteria work together to digest food and keep you healthy.

- Competing for Space and Food: Microorganisms fight for space and nutrients. In a drop of water, bacteria might race to eat sugar before algae do, or they might release chemicals to push others away.

- Living Together: Some microorganisms form groups called biofilms (like a slimy layer on rocks or teeth). In biofilms, bacteria stick together, share food, and protect each other from harm.

- Predator and Prey: Bigger microorganisms, like amoebas, eat smaller ones, like bacteria, by swallowing them. It’s like a tiny food chain in the microscopic world!

- Chemical Communication: Bacteria use chemicals to “talk” to each other (called quorum sensing). For example, they might signal, “There’s enough of us—let’s make a biofilm!” or “Attack that harmful bacteria!”

4. Share your questions

Answer: Seeing the invisible world and learning about microorganisms sparks so many questions! Here are some questions you might have, and you can add your own:

- What do microorganisms eat to stay alive?

- Can microorganisms see or feel each other, or do they just bump into things?

- Why are some bacteria helpful (like in curd) and others harmful (like causing diseases)?

- How do microorganisms survive in tough places, like hot springs or salty water?

- Could we use microorganisms to clean up pollution or make new medicines?

- Do microorganisms ever “sleep” or rest, or are they always active?

- What would happen if all microorganisms disappeared from Earth?

Keep the curiosity alive

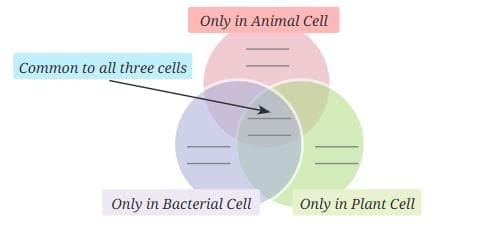

Q1. Various parts of a cell are given below. Write them in the appropriate places in the following diagram: Nucleus, Cytoplasm, Chloroplast, Cell wall, Cell membrane, Nucleoid.

Answer:

Common to Plant, Animal and Bacterial Cells:

- Cytoplasm: Fills the cell and holds organelles in both plant and animal cells.

- Cell membrane: Controls what enters and exits in both plant and animal cells.

- Nucleus: The control center with DNA, found in both plant and animal cells.

Only in Plant Cells:

- Chloroplast: Found only in plant cells, helps in photosynthesis to make food.

- Cell wall: Found only in plant cells, gives strength and support.

Only in Animal Cells:

- None of the given parts are exclusive to animal cells. (Animal cells may have other parts like centrioles, but they’re not in the list.)

Only in Bacterial Cells:

- Nucleoid: Found only in bacterial cells, it’s a region where DNA is stored, not inside a proper nucleus.

- Cell wall: Bacteria have a cell wall, but it’s different from a plant’s cell wall in composition.

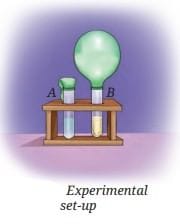

Q2. Aanandi took two test tubes and marked them A and B. She put two spoonfuls of sugar solution in each of the test tubes. In test tube B, she added a spoonful of yeast. Then she attached two incompletely inflated balloons to the mouth of each test tube. She kept the set-up in a warm place, away from sunlight.

(i) What do you predict will happen after 3–4 days? She observed that the balloon attached to test tube B was inflated. What can be a possible explanation for this?

(a) Water evaporated in test tube B and filled the balloon with water vapour.

(b) The warm atmosphere expanded the air inside test tube B, which inflated the balloon.

(c) Yeast produced a gas inside test tube B which inflated the balloon.

(d) Sugar reacted with warm air, which produced gas, eventually inflating the balloon.

Answer:

(i) Prediction and Explanation:

After 3–4 days, the balloon on test tube B will inflate, but the balloon on test tube A will not. The correct explanation is:

(c) Yeast produced a gas inside test tube B which inflated the balloon.

Yeast, a type of fungus, breaks down sugar in warm conditions, producing carbon dioxide gas. This gas fills the balloon, making it inflate. Test tube A has no yeast, so no gas is produced, and the balloon stays the same.

(ii) She took another test tube, 1/4 filled with lime water. She removed the balloon from test tube B in such a manner that the gas inside the balloon did not escape. She attached the balloon to the test tube with lime water and shook it well. What do you think she wants to find out?

Ans: Purpose of Lime Water Test:

Aanandi wants to find out if the gas in the balloon from test tube B is carbon dioxide. When she shakes the gas with lime water, if the lime water turns milky, it confirms the gas is carbon dioxide, as lime water reacts with carbon dioxide to form a cloudy substance. This shows yeast produced carbon dioxide in test tube B.

Q3. A farmer was planting wheat crops in his field. He added nitrogen-rich fertiliser to the soil to get a good yield of crops. In the neighbouring field, another farmer was growing bean crops, but she preferred not to add nitrogen fertiliser to get healthy crops. Can you think of the reasons?

Answer:

- The farmer growing beans didn’t add nitrogen fertiliser because bean plants have special bacteria called Rhizobium in their root nodules.

- These bacteria take nitrogen from the air and turn it into nutrients the bean plants can use, making the soil naturally rich in nitrogen.

- Wheat crops don’t have these bacteria, so the other farmer needed fertiliser to add nitrogen for good growth.

- By growing beans, the farmer saves money and keeps the soil healthy without chemicals.

Q4. Snehal dug two pits, A and B, in her garden. In pit A, she put fruit and vegetable peels and mixed it with dried leaves. In pit B, she dumped the same kind of waste without mixing it with dried leaves. She covered both the pits with soil and observed after 3 weeks. What is she trying to test?

Answer:

- Snehal is testing how dried leaves affect the breakdown of fruit and vegetable peels into manure.

- In pit A, mixing peels with dried leaves helps microorganisms (like bacteria and fungi) decompose the waste faster, turning it into nutrient-rich manure.

- In pit B, without dried leaves, decomposition is slower because microorganisms work less effectively. She wants to see if adding dried leaves makes better manure in less time.

Q5. Identify the following microorganisms:

(i) I live in every kind of environment, and inside your gut.

(ii) I make bread and cakes soft and fluffy.

(iii) I live in the roots of pulse crops and provide nutrients for their growth.

Answer:

Based on the chapter, the microorganisms are:

(i) Bacteria: They live in all environments, like water, soil, air, and inside our gut, helping with digestion (as mentioned in Section 2.4).

(ii) Yeast: This fungus makes bread and cakes soft and fluffy by producing carbon dioxide gas during fermentation (as in Activity 2.8).

(iii) Rhizobium: This bacterium lives in root nodules of pulse crops (like beans) and traps nitrogen from the air to make nutrients for plants

Q6. Devise an experiment to test that microorganisms need optimal temperature, air, and moisture for their growth.

Answer:

Experiment to Test Microorganism Growth:

- Materials: 3 small bowls, bread pieces, water, yeast powder, a warm place, a refrigerator, a sealed plastic bag.

- Steps:

- Take three bowls (A, B, C) and place a small piece of bread in each.

- In bowl A, add a pinch of yeast and a few drops of water, then cover it and keep it in a warm place (like near a window).

- In bowl B, add a pinch of yeast and water, then put it in a refrigerator (cold, moist, with air).

- In bowl C, add a pinch of yeast, but don’t add water, and seal it in a plastic bag (warm, dry, no air).

- Observe all bowls after 2–3 days.

- Expected Results:

- Bowl A (warm, moist, with air) will show the most growth, like mould or fluffy yeast, because microorganisms grow best in warm, moist conditions with air.

- Bowl B (cold) will show little or no growth, as cold slows microorganisms (like in Activity 2.9 with cold milk).

- Bowl C (dry, no air) will show no growth, as microorganisms need moisture and air.

- Conclusion: Microorganisms need optimal temperature (warm), moisture, and air to grow well.

Q7. Take 2 slices of bread. Place one slice in a plate near the sink. Place the other slice in the refrigerator. Compare after three days. Note your observations. Give reasons for your observations.

Answer:

Observations:

- The bread slice near the sink will likely have mould (green or white patches) after three days.

- The bread slice in the refrigerator will have little or no mould and look mostly unchanged.

Reasons:

- Near the sink, the bread is in a warm, moist place with air, perfect for microorganisms like fungi to grow and form mould (like in Section 2.4, where microbes grow on food).

- In the refrigerator, the cold temperature slows down microorganism growth, preventing mould (like cold milk not curdling in Activity 2.9). Microorganisms need warmth and moisture to grow, which the refrigerator lacks.

Q8. A student observes that when curd is left out for a day, it becomes more sour. What can be two possible explanations for this observation?

Answer:

Two reasons why curd becomes more sour when left out for a day:

- Bacteria Keep Working: Curd has bacteria like Lactobacillus that feed on milk sugar (lactose) and produce lactic acid, making curd sour. When left out in warm conditions, these bacteria multiply and produce more lactic acid, increasing sourness.

- Warm Temperature Helps Bacteria: Warm conditions speed up bacterial activity, causing them to ferment the curd faster and produce more lactic acid. This makes the curd taste more sour.

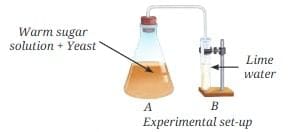

Q9. Observe the set-up given in Fig. 2.15 and answer the following questions.

(i) What happens to the sugar solution in flask A?

(ii) What do you observe in test tube B after four hours? Why do you think this happened?

(iii) What would happen if yeast was not added in flask A?

Answer:

(i) What Happens to the Sugar Solution in Flask A?

The sugar solution in flask A, mixed with yeast, ferments. Yeast breaks down the sugar, producing carbon dioxide gas and a small amount of alcohol, making the solution bubbly.

(ii) What Do You Observe in Test Tube B After Four Hours? Why?

In test tube B, the lime water turns milky after four hours. This happens because the carbon dioxide gas from flask A (produced by yeast) reacts with lime water, forming a cloudy substance. This confirms yeast produced carbon dioxide (similar to the balloon test in Question 2).

(iii) What Would Happen if Yeast Was Not Added in Flask A?

If yeast was not added to flask A, no carbon dioxide gas would be produced because yeast is needed to ferment the sugar. The sugar solution would stay unchanged, and the lime water in test tube B would not turn milky.

Discover, design, and debate

Q1. India has a long history of biogas production. One of our oldest biogas plant was set up in late 1850s. Find out about the Biogas Program initiated by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Government of India.

Ans: Discover: India has been using biogas for a long time, starting in the late 1850s! Biogas is a clean fuel made from organic waste like cow dung, kitchen scraps, and plant material. The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) in India runs the National Biogas and Manure Management Programme (NBMMP)to help people set up biogas plants in rural and semi-urban areas. This program started to provide clean energy for cooking, lighting, and even small power needs, while also reducing pollution and helping farmers.Key Points about the Biogas Program:

- Purpose: To make clean fuel from organic waste, improve sanitation, reduce greenhouse gases, empower women by reducing cooking smoke, and create jobs in villages.

- How It Works: Biogas is produced through a process called anaerobic digestion, where microorganisms break down organic waste (like cow dung) without oxygen, producing a gas (55-65% methane, 35-44% carbon dioxide) and nutrient-rich slurry (bio-manure).

- Types of Biogas Plants: Small plants (1-25 m³/day) for households and medium plants (25-2500 m³/day) for power generation (3-250 kW) or heating/cooling.

- Benefits: Provides clean cooking fuel (like LPG), reduces indoor air pollution, saves money on LPG refills, and produces bio-manure to replace chemical fertilizers.

- Support: The government gives subsidies (financial help) to families and farmers to set up biogas plants. For example, extra support is given in Northeast India, hilly areas, and for SC/ST communities.

- Achievements: By 2014, about 47.5 lakh biogas plants were installed, with a target of 1.1 lakh more in 2014-15. The program continues until 2025-26 with a budget of ₹858 crore for biogas and other bioenergy projects.

- Design: Imagine you’re designing a small biogas plant for a village home. It needs 50-60 m² of space, a regular supply of cow dung, and water to mix into a slurry. Draw a simple model showing a digester tank, gas outlet, and slurry storage. Think about how to make it easy to use for a family!Debate: Discuss with friends: “Should every village in India have a biogas plant?” Consider benefits (clean fuel, less pollution) versus challenges (cost, maintenance, availability of waste).

Q2. Fermented food items like fermented soybeans and fermented bamboo shoots are consumed as traditional food in some parts of India. With the help of your parents and teachers, list some traditional food items from your area that utilise the process of fermentation. Investigate the ingredients used in the preparation of these fermented food items; the method of preparing them; the microorganism responsible for the fermentation of the food, and the cultural and nutritional importance of the fermented food.

Ans: Discover: Fermentation is a process where microorganisms like yeast or bacteria break down sugars and starches in food to produce acids, alcohol, or gases. This makes food tasty, easier to digest, and longer-lasting. In India, many traditional foods are fermented, especially in different regions. Let’s explore some examples from various parts of India, as you can ask your parents or teachers about local foods in your area.

Examples of Traditional Fermented Foods:

Dahi (Curd): Common across India.

- Ingredients: Milk, starter culture (a bit of old curd with live bacteria).

- Preparation: Boil milk, cool it slightly, add a spoonful of curd, and let it sit in a warm place for 6-8 hours until it thickens.

- Microorganisms: Lactic acid bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus species) turn milk sugar (lactose) into lactic acid, giving curd its tangy taste.

- Cultural Importance: Used in daily meals, religious rituals, and festivals (e.g., curd rice in South India). It’s cooling and loved in summers.

- Nutritional Importance: Rich in probiotics (good bacteria) that help digestion, boost immunity, and provide calcium and protein.

Idli/Dosa (South India):

- Ingredients: Rice, urad dal (black gram), water, salt.

- Preparation: Soak rice and dal separately, grind into a batter, mix, and let it ferment for 8-12 hours in a warm place until bubbly. Cook as idlis (steamed) or dosas (pancakes).

- Microorganisms: Lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus) and yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) ferment the batter, producing carbon dioxide for fluffiness.

- Cultural Importance: A staple breakfast in South India, served with chutney and sambar, symbolizing simple, healthy eating.

- Nutritional Importance: High in carbohydrates, protein, and probiotics; easy to digest and low in fat.

Gundruk (Northeast India, e.g., Sikkim, Darjeeling):

- Ingredients: Leafy greens (mustard, radish, or cauliflower leaves).

- Preparation: Leaves are wilted, crushed, packed tightly in a container, and fermented for 7-10 days. Then dried and stored.

- Microorganisms: Lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus plantarum) ferment the leaves, producing lactic acid.

- Cultural Importance: A traditional dish in Northeast India, often eaten as a side dish or in soups, reflecting local farming culture.

- Nutritional Importance: Rich in vitamins, minerals, and probiotics; preserves greens for year-round use.

Kinema (Fermented Soybeans, Northeast India):

- Ingredients: Soybeans.

- Preparation: Soak soybeans, boil, wrap in leaves, and ferment for 1-3 days in a warm place until sticky.

- Microorganisms: Bacillus subtilis ferments the beans, giving a unique smell and texture.

- Cultural Importance: A protein-rich dish in Sikkim and Northeast, eaten with rice, part of tribal food traditions.

- Nutritional Importance: High in protein, vitamins, and probiotics; a meat substitute for vegetarians.

Activity: Ask your parents or teachers about fermented foods in your area (e.g., dhokla in Gujarat, bamboo shoot pickle in Northeast, or handia in Odisha). List at least two local foods, their ingredients, and how they’re made.

Design: Create a poster showing how one fermented food (e.g., idli) is prepared, labeling the ingredients and steps. Include a fun fact about its cultural importance.

Debate: Discuss with classmates: “Are fermented foods healthier than non-fermented foods?” Talk about taste, nutrition, and shelf life.

Q3. Study the different parts of a macro fungus mushroom using a magnifying glass and microscope/foldscope. Take the help of students from senior classes and explore the internal structure of different parts of mushrooms under the microscope/foldscope in your school laboratory.

Ans: Discover: Mushrooms are macro fungi, meaning they’re large enough to see without a microscope. They’re not plants but belong to the fungi kingdom. Common edible mushrooms (e.g., button or oyster mushrooms) have parts you can study with a magnifying glass and a microscope or foldscope (a low-cost paper microscope). Ask senior students or teachers to help in your school lab.

Parts of a Mushroom (using a magnifying glass):

- Cap (Pileus): The top, umbrella-like part, often round or flat, protects the gills. Colors vary (white, brown, etc.).

- Gills (Lamellae): Thin, blade-like structures under the cap, where spores (tiny seeds) are produced. Look like lines or folds.

- Stalk (Stipe): The stem that holds up the cap, giving support. It may have a ring or skirt.

- Ring (Annulus): A skirt-like structure on the stalk, left from the veil that covers young mushrooms (not all mushrooms have it).

- Base (Volva): The bottom of the stalk, sometimes bulb-like or cup-shaped (seen in some mushrooms like Amanita).

Internal Structure (using a microscope/foldscope):

- Spores: Tiny reproductive cells in the gills. Under a microscope, they look like small ovals or circles (4-6 µm in size for some mushrooms). Their color and shape help identify the mushroom.

- Hyphae: Thread-like structures forming the mushroom’s body (mycelium). Under a microscope, they look like thin, branching tubes.

- Basidia: Club-shaped cells in the gills where spores are formed. They’re visible under a microscope as small, elongated structures.

How to Study:

- Get a fresh mushroom (e.g., button mushroom from a market).

- Use a magnifying glass to observe the cap, gills, stalk, and ring clearly.

- In the lab, with help from seniors or teachers:

- Cut a thin slice of the cap or gills using a blade (be careful!).

- Place the slice on a slide, add a drop of water, and cover with a coverslip.

- Observe under a microscope or foldscope at low (40x) and high (100x) magnification to see spores, hyphae, or basidia.

- Draw what you see and label the parts.

Design: Sketch a mushroom and label its parts (cap, gills, stalk, ring). Create a small chart showing what spores and hyphae look like under a microscope.

Debate: Discuss: “Should we eat all mushrooms we find in the wild?” Talk about why some mushrooms are edible and others are poisonous, using your observations of their structure.

Note: Always handle mushrooms with care, as some are toxic. Use only store-bought or lab-provided mushrooms for study.

Q4. Interact with an entrepreneur and learn the steps for cultivation of mushroom.

Ans: Discover: Mushroom cultivation is a great way to grow healthy food using less land, water, and energy. It’s a popular business in India, especially for oyster or button mushrooms. By talking to a mushroom entrepreneur (or researching with your teacher’s help), you can learn the steps to grow mushrooms and start a small business.

Steps for Mushroom Cultivation (e.g., Oyster Mushrooms):

- Choose the Mushroom Type: Select an edible mushroom like oyster (Pleurotus species) or button (Agaricus bisporus), which are easy to grow and popular.

- Prepare the Spawn: Spawn is like the “seed” of mushrooms (mycelium grown on grains). Buy good-quality spawn from a trusted supplier or lab.

- Select a Substrate: Use agricultural waste like straw, sawdust, or corn stalks as the growing medium. Soak straw in water and boil or sterilize it to kill unwanted germs.

- Mix Spawn with Substrate: In a clean room, mix the spawn with the sterilized substrate and pack it into polythene bags with small holes for air.

- Incubation: Keep the bags in a dark, warm place (25-30°C) for 15-20 days. The mycelium (white, thread-like growth) spreads in the substrate.

- Fruiting: Move the bags to a cool, humid place (20-25°C, 80-90% humidity) with some light. Spray water daily to keep it moist. Mushrooms start growing in 5-10 days.

- Harvest: When mushroom caps are fully open, cut them at the base. You can harvest 2-3 times from one bag.

- Sell or Use: Sell fresh mushrooms in markets or dry them for longer storage. The leftover substrate (spent mushroom substrate) can be used as compost or for biogas production.

Tips from Entrepreneurs:

- Keep everything clean to avoid contamination by other fungi or bacteria.

- Maintain proper temperature and humidity (use a thermometer and water sprays).

- Start small (e.g., 10-20 bags) to learn, then scale up for business.

- Market mushrooms to local shops, restaurants, or online platforms.

Cultural and Economic Importance: Mushroom farming is eco-friendly, uses waste materials, and provides jobs. Mushrooms are nutritious (rich in protein, vitamins) and a meat substitute for vegetarians.

Design: Create a flowchart showing the steps of mushroom cultivation, from spawn to harvest. Add pictures or drawings to make it colorful.

Debate: Discuss: “Can mushroom farming be a good business for young people in villages?” Talk about costs, profits, and environmental benefits versus challenges like learning the process or finding buyers.