Short Answer Questions

Q1. How does cycling uphill and downhill illustrate the role of different forces?

Answer: Uphill, gravity and friction oppose motion making it harder to pedal, while downhill gravity helps motion and friction is smaller, so the cycle speeds up easily.

Q2. Why do we say forces arise from interactions between two objects?

Answer: A force needs two partners, like a hand pushing a table or a bat hitting a ball, because one object acts on another to create the push or pull.

Q3. How can balanced and unbalanced forces explain why an object stays at rest or starts moving?

Answer: If forces are balanced, there is no change in motion and the object stays at rest or moves steadily; if they are unbalanced, the object speeds up, slows down, or changes direction.

Q4. How can you show in class that a force can change the shape of an object?

Answer: You can stretch a rubber band or squeeze clay to show that applying a force changes the object’s shape without necessarily moving it.

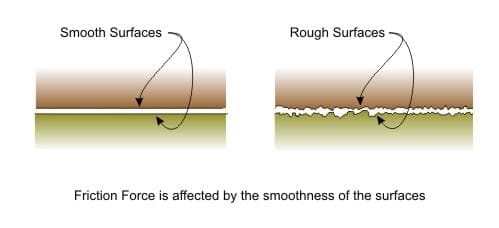

Q5. What everyday observations show that friction depends on the nature of surfaces?

Answer: A box slides farther on a smooth tile than on rough carpet because smooth surfaces have less friction and rough surfaces have more friction.

Q6. How does air or water resistance affect moving objects like cyclists or boats?

Answer: Air and water push back against motion as drag, so cyclists and boats go faster when they are streamlined to reduce this resisting force.

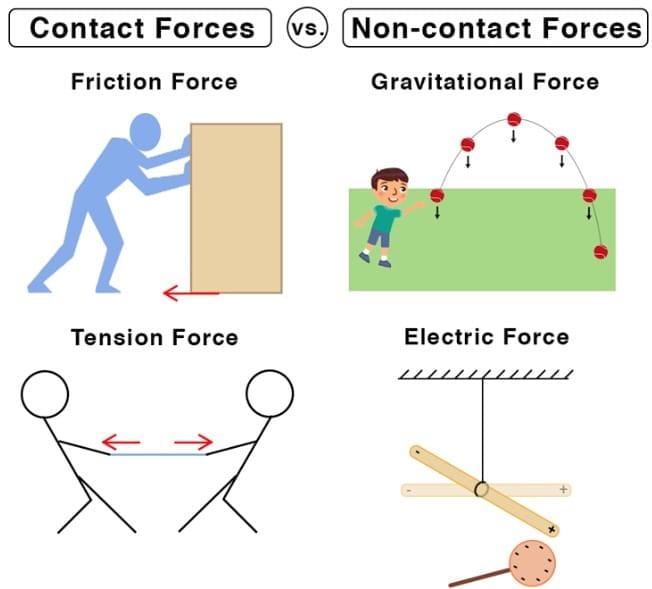

Q7. How can you identify the type of force acting in a given situation: contact or non-contact?

Answer: If objects touch, like pushing a door or rubbing hands, it is a contact force; if they act without touching, like magnets attracting or gravity pulling, it is a non-contact force.

Q8. How can a spring balance be used to compare the weights of two objects?

Answer: Hang each object on the hook one by one and read the scale in newtons; the object that stretches the spring more and gives a higher reading has greater weight.

Q9. Why is “10 kg” not a correct scientific way to report weight and what should we use instead?

Answer: Kilogram is a unit of mass, while weight is a force and should be reported in newtons; for example, a 10 kg mass weighs about 98–100 N on Earth.

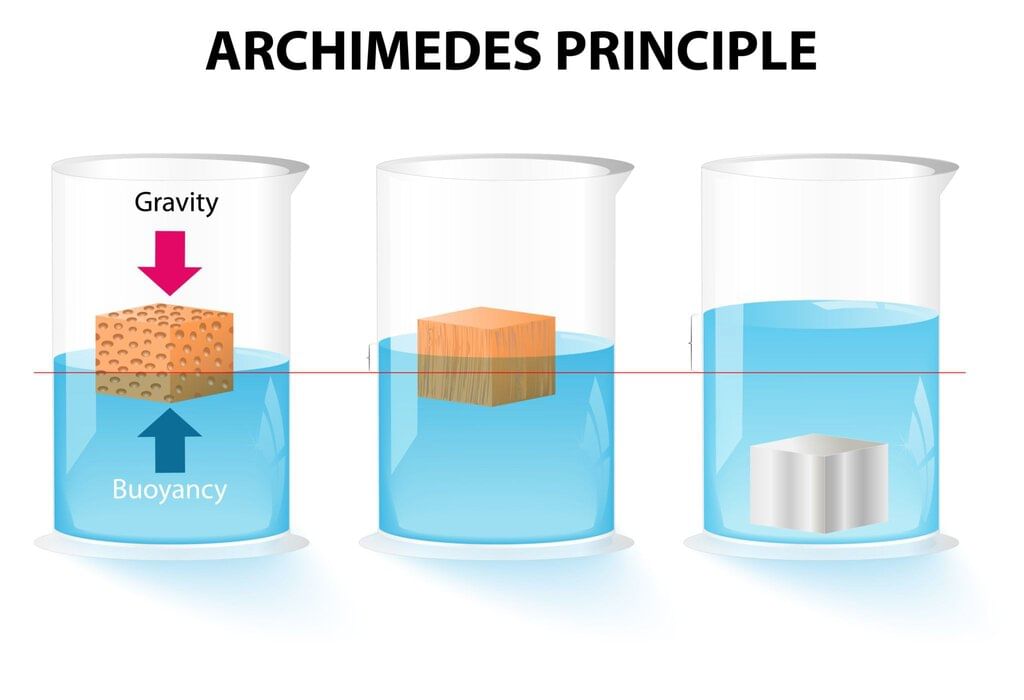

Q10. What factors decide whether an object will float or sink in water?

Answer: If the buoyant force equals or exceeds the object’s weight, it floats; if the weight is greater than the buoyant force, it sinks.

Q11. How does Archimedes’ principle help explain floating?

Answer: It states that the upward buoyant force equals the weight of the displaced liquid, so an object floats when it displaces water weighing as much as the object itself.

Q12. Why can some rocks like pumice float on water even though most rocks sink?

Answer: Pumice contains many air pockets that make it less dense than water, so the buoyant force balances its weight and it floats.

Long Answer Questions

Q1. Explain with examples how forces can act together on an object and still produce no change in motion, and describe what happens when this balance is disturbed.

Answer:

- When equal and opposite forces act on an object, they are balanced and cause no change in motion; for example, a book resting on a table has its weight balanced by the table’s upward push.

- A cyclist moving at a steady speed also experiences balanced forces, as the push from pedaling matches friction and air resistance. If the cyclist pedals harder, the forward force becomes larger than resistive forces, and speed increases.

- If the cyclist stops pedaling, resistive forces become greater and the cycle slows down. Therefore, any change in balance leads to acceleration or deceleration.

Q2. Describe an investigation to show that friction depends on the nature of surfaces and how adding weight affects friction, including steps and observations.

Answer:

- Place a wooden block on a smooth tile and pull it with a spring balance to start motion, noting the reading. Repeat on a rough surface like sandpaper and observe that a larger force is needed on the rough surface.

- Next, add weights on the block and repeat on the same surface; the spring balance shows higher readings as weight increases. Record all values in a table to compare how surface type and load change friction.

- This shows friction increases with roughness and with greater normal force due to added weight.

Q3. Explain how direction changes in motion are caused by forces, using at least two real-world examples without changing speed much.

Answer:

- A force can change direction even if speed stays nearly the same, like when turning a bicycle’s handle around a bend. The rider applies a sideways force through the handle and tires on the road, causing the cycle to curve.

- In cricket, a fielder deflects a fast-moving ball with a gentle push to guide it toward the stumps without greatly changing its speed. Similarly, a car’s tires provide lateral frictional force to take a turn safely.

- These examples show that force is needed to change direction, not just speed.

Q4. Compare and contrast contact forces and non-contact forces by explaining how they act, the conditions needed, and their effects in everyday situations.

Answer:

- Contact forces require touching, like muscular force pushing a cart or friction slowing a sliding box; they arise from interactions between surfaces or through tools.

- Non-contact forces act at a distance, such as magnetic force attracting pins, electrostatic force pulling paper bits to a charged comb, or gravity pulling objects downward.

- Contact forces often depend on surface properties and pressure, while non-contact forces depend on material properties and distance. In daily life, opening a drawer uses contact force, while a magnet on a fridge shows non-contact force. Both kinds can start motion, stop motion, or change direction.

Q5. Explain how to read range and least count on a spring balance and why selecting the right range matters for accurate measurements.

Answer:

- The range is the maximum weight a spring balance can measure, such as 0–10 N, and using a load beyond it can damage the spring. The least count is the smallest division you can read; if 1 N is divided into 5 parts, the least count is 0.2 N.

- Choosing the right range ensures the pointer stays within the scale and improves accuracy. A balance with a smaller least count lets you measure small differences more precisely.

- Proper selection and reading help compare weights reliably in experiments.

Q6. Discuss how mass and weight differ and why the same object can have different weights on different planets while its mass remains unchanged.

Answer:

- Mass is the amount of matter in an object and does not change with location, while weight is the force due to gravity and depends on the planet’s gravitational pull.

- On Earth, a 1 kg mass weighs about 10 N, but on the Moon it weighs about 1.6 N because gravity is weaker there. On Jupiter, the same 1 kg mass would weigh much more due to stronger gravity.

- Scientists use kilograms (kg) for mass and newtons (N) for weight to avoid confusion. This distinction is important in scientific measurements and space exploration.

Q7. Describe the forces acting on an object floating in water and explain how changing the object’s shape can affect floating using the idea of displaced liquid.

Answer:

- A floating object experiences gravity downward and an upward buoyant force from the water; at float, these forces balance. Archimedes’ principle states the buoyant force equals the weight of the displaced water.

- By changing shape to increase volume without much change in mass, the object displaces more water and can float better, like a flat boat-shaped sheet versus a tight ball of the same material.

- This is why ships made of metal can float—they displace a lot of water due to their hollow shape. The balance of weight and displaced water decides floating.

Q8. Explain with examples how multiple forces can act simultaneously in motion, such as during cycling on a windy day, and how net force determines the outcome.

Answer:

- While cycling, the rider’s push provides a forward force, friction at the tires helps grip and move, air resistance opposes motion, and gravity acts downward with the road pushing upward.

- On a windy day, wind can add a backward or forward force depending on its direction. The combined effect of all these forces creates a net force, which decides if the cyclist speeds up, slows down, or maintains speed.

- If the rider’s push plus helpful wind is greater than resistive forces, speed increases; if not, the cycle slows. Understanding net force helps explain real-life motion in changing conditions.