Page 48

Questions (Implied from Reema’s Curiosity):

Q1: Since when have humans been counting?

Ans: Humans have been counting since at least the Stone Age (around 10,000 years ago) to track quantities of food, livestock, trade goods, ritual offerings, and to predict events like lunar phases or seasons.

Q2: What was their need for counting?

Ans: The need arose to quantify resources (e.g., food, livestock), manage trade, record ritual offerings, and track time for events like new moons or seasonal changes.

Q3: What were they counting?

Ans: They counted food items, animals in livestock, trade goods, ritual offerings, and days for calendrical purposes.

Q4: Since when have people been writing numbers in the modern form?

Ans: The modern form (Hindu numerals, 0–9) originated in India around 2000 years ago, with the earliest known use in the Bakhshali manuscript (c. 3rd century CE). Aryabhata (c. 499 CE) formalized their use, and they spread globally by the 17th century.

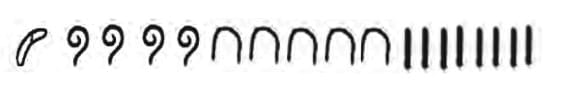

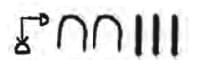

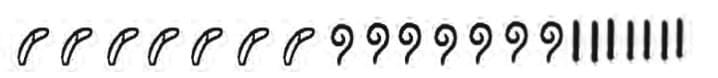

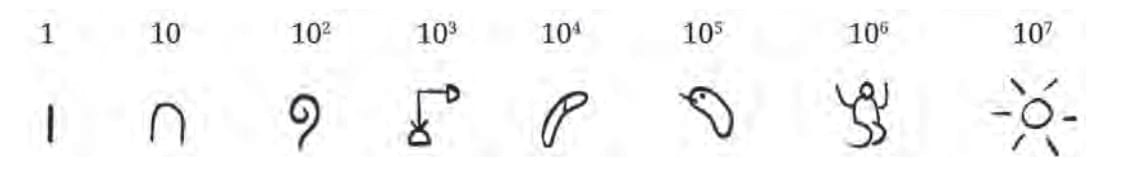

Q5: How would the Mesopotamians have written 20, 50, 100?

Ans: The Mesopotamian (Babylonian) system was a base-60 positional system using symbols for 1 (⟐) and 10 (⟐). Numbers were grouped into powers of 60, with a placeholder for zero in later periods.

Assuming the simplified notation from Section 3.4:

- 20: 20 = 20 × 1 = ⟐⟐ (two 10s).

- 50: 50 = 5 × 10 = ⟐⟐⟐⟐⟐ (five 10s).

- 100: 100 = 1 × 60 + 40 × 1 = ⟐,⟐⟐⟐⟐ (one 60 and four 10s).

Note: Commas separate place values for clarity, though spacing was inconsistent in practice.

Page 51

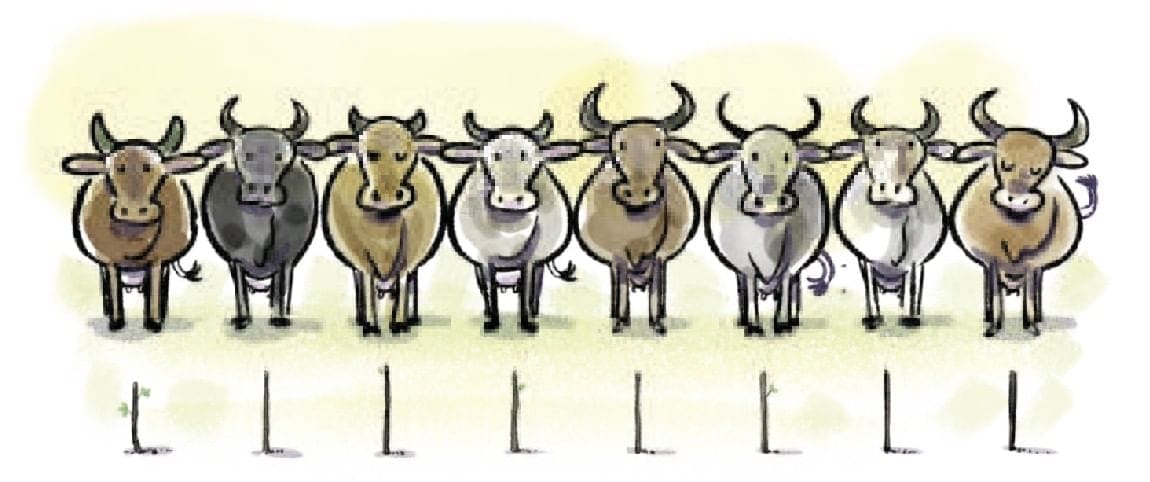

Q1. How do we ensure that all cows have returned safely aftergrazing?

Ancient humans used sticks to count their herd of cows through a very practical, physical method:

- For each cow in the herd, one stick was set aside.

- After the cows went out to graze, the herder would collect a stick for each cow that returned.

- If a stick remained with no cow to match it, that meant a cow was missing; if all sticks matched, then all cows had returned.

Q2. Do we have fewer cows than our neighbour?

Ancient humans could compare herds without words by using physical objects—typically sticks, stones, or tallies—to represent each cow. Here’s how they would determine if they had fewer cows than their neighbor:

- Each person would create a collection of sticks, one stick for each cow in their herd.

- They would then place their collections side by side.

- By pairing off the sticks one by one from each herd, they could see which collection finished first.

- If your pile of sticks was exhausted before your neighbor’s, this showed you had fewer cows.

- The difference in the length (or count) of the two piles directly told you how many fewer cows you had.

This method worked because it relied entirely on one-to-one correspondence, requiring no written numbers or words—just an exact physical representation.

Q3. If there are fewer, how many more cows would we need so that we have the same number of cows as our neighbour?

If you find that you have fewer cows than your neighbor after comparing your piles of sticks (one stick per cow):

- Take your pile of sticks and your neighbor’s pile of sticks.

- Pair them one-to-one as far as possible.

- The number of sticks left (unpaired) in your neighbor’s pile tells you exactly how many cows you would need to add to your herd to have the same number as your neighbor.

- In other words, you simply count the extra sticks in your neighbor’s pile after pairing, and that is the answer.

How will you use such sticks to answer the other two questions (Q2 and Q3)?

Ans: Same as above.

Page 53

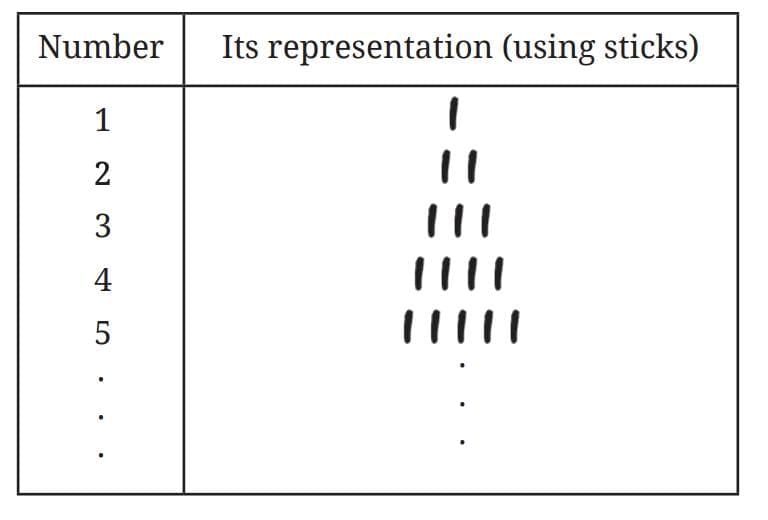

Q: How many numbers can you represent in this way using the sounds of the letters of your language?

Ans: Using only the sounds of English letters, you can represent at most 26 distinct numbers, since there are 26 letters. Letters don’t naturally map to numbers, so without creating combinations or a naming system, this method is limited. For numbers beyond 26, you’d need to combine letter sounds or use a more complex system.

Q: Do you see a way of extending this method to represent bigger numbers as well? How?

Ans: To represent bigger numbers using letter sounds, we need a fixed, ordered system—called a number system. While using letter sounds is convenient, it’s limited as there are only 26 letters. To extend it for bigger numbers, we must combine letter sounds or symbols to create a longer, standard sequence—just like Roman or Hindu number systems do.

Page 54

Figure it Out

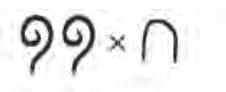

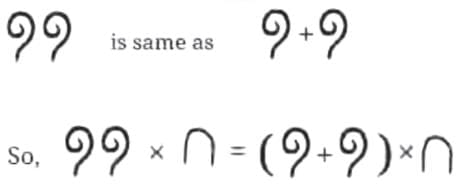

Q1. Suppose you are using the number system that uses sticks to represent numbers, as in Method 1. Without using either the number names or the numerals of the Hindu number system, give a method for adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing two numbers or two collections of sticks.

Ans: Using sticks (Method 1) to perform arithmetic operations:

- Addition:

Combine two collections of sticks into a single larger collection. The total number of sticks now represents the sum. - Subtraction:

Remove sticks from one collection to match the number in another. The remaining sticks represent the difference. - Multiplication:

Think of multiplication as repeated addition. For example, to multiply 3 by 4, create 4 groups each having 3 sticks, then combine all the groups into one pile and count sticks. - Division:

Divide a collection of sticks into equal smaller groups. The number of groups you can make represents the quotient, and leftover sticks (if any) are the remainder.

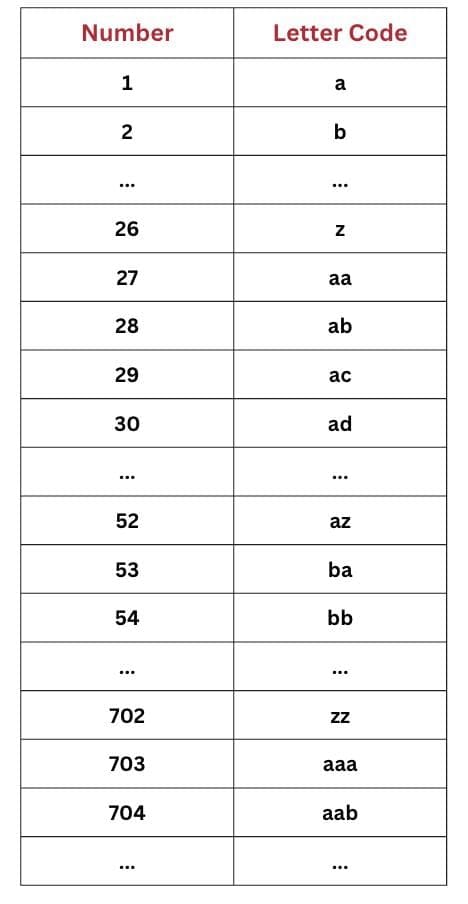

Q2. One way of extending the number system in Method 2 is by using strings with more than one letter—for example, we could use ‘aa’ for 27. How can you extend this system to represent all the numbers? There are many ways of doing it!

Ans: Extending a letter-based number system like Method 2 (‘a’ to ‘z’ representing 1 to 26):

To represent numbers beyond 26, use combinations of letters similar to how letters form words. For example:

- ‘a’ = 1, ‘b’ = 2, …, ‘z’ = 26

‘aa’ = 27, ‘ab’ = 28, ‘ac’ = 29, and so on.

‘aa’ = 27, ‘ab’ = 28, ‘ac’ = 29, and so on.

This works like a base-26 system, where each position represents powers of 26, similar to how digits work in the decimal system (base-10).

You can keep extending to three letters, four letters, etc., allowing representation of all natural numbers.

Q3. Try making your own number system.

Ans: Do it Yourself!

Hint: Try these steps:

- Choose simple symbols or objects (like stones, shells, hand signs, or colors).

- Assign each symbol a specific value, starting from 1.

- Decide on a method to combine symbols to form larger numbers — for example, repetition to indicate quantity (like tally marks), or place value methods (like grouping symbols in sets).

- Create rules for arithmetic operations based on how you combine or separate these symbols.

For instance, you could use colored beads where each color counts as a certain number, and putting beads together adds their values; different bead strings could represent larger numbers.

This approach both honours ancient counting methods and encourages creative thinking about the concept of numbers.

Page 56

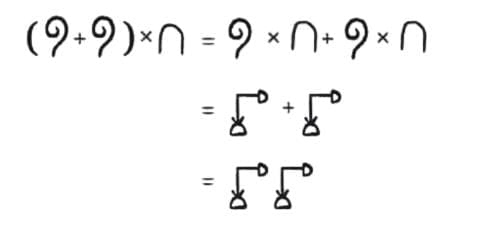

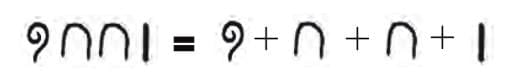

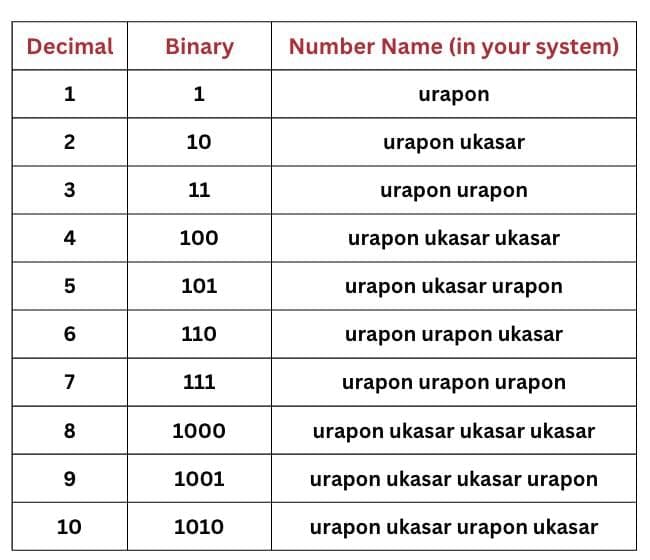

Q: Can you see how their number names are formed?

Ans: The Gumulgal number system forms number names by counting in twos, combining the words “urapon” (1) and “ukosar” (2):

- 1: urapon

- 2: ukosar

- 3: ukosar-urapon (2 + 1)

- 4: ukosar-ukosar (2 + 2)

- 5: ukosar-ukosar-urapon (2 + 2 + 1)

- 6: ukosar-ukosar-ukosar (2 + 2 + 2)

Q: Can you see how the names of the other numbers are formed?

Ans: The pattern uses “ukosar” for each group of 2 and “urapon” for an additional 1, building numbers additively based on twos and ones.

- 3 = 2 + 1,

- 4 = 2 + 2,

- 5 = 2 + 2 + 1,

- 6 = 2 + 2 + 2.

Gumulgal called any number greater than 6 ras.

Page 57

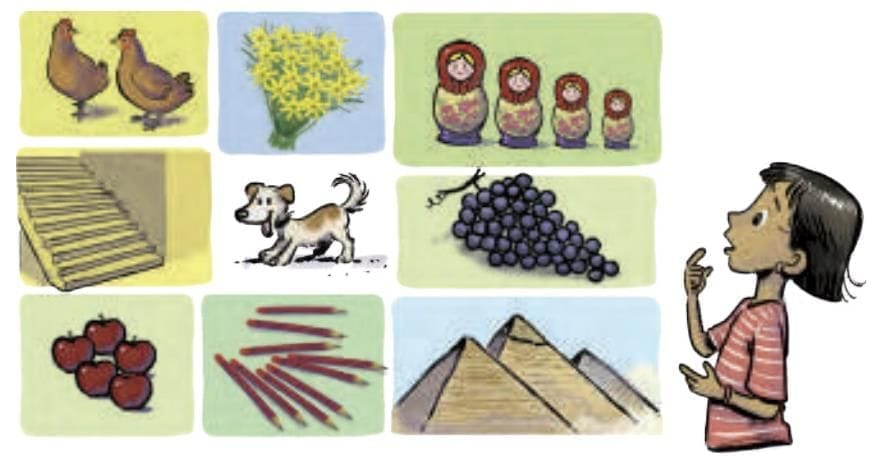

Q: Quickly count the number of objects in each of the following boxes:

Ans: Let’s count:

Observation:

- You can instantly recognize smaller quantities (1–4).

- For larger groups (like grapes, flowers, sticks), you likely had to count or estimate.

- This supports the idea that human perception easily handles up to 4 items instantly, but beyond that, counting is needed.

Page 58

Q: What could be the difficulties with using a number system that counts only in groups of a single particular size? How would you represent a number like 1345 in a system that counts only by 5s?

1. Lack of Flexibility

- You can only count in fixed steps (e.g., 5, 10, 15…), so it’s hard to represent numbers that aren’t exact multiples of that size,

- Example: 1,234 can’t be represented accurately.

2. Representation Becomes Lengthy or Complicated

- To represent numbers like 1, 2, or 3, you’d have to invent special symbols or combinations, since they don’t fit in the group size.

- Example: Representing the number 3 might need a symbol like “~~~” (three dashes), or a new symbol altogether, adding unnecessary complexity for small values.

3. Complex Arithmetic Systems

- Adding, subtracting, or comparing numbers becomes harder because there’s no positional value system or digits.

- Example: In our normal number system, adding 243 and 159 is easy because we use place values.

For example:

243 = 2 hundreds + 4 tens + 3 ones

159 = 1 hundred + 5 tens + 9 ones

We can align the digits and add them column by column. - But in a system where you only use symbols or count in fixed steps (like 5s), there’s no such place value.

For example, if ‘A’ = 5, then:- A + A = 10 — but there’s no clear way to write 10 unless you define a new symbol for it.

- AAAAA (5 times A) = 25, and AAAAAA = 30 — but to compare them, you have to count each symbol every time.

4. Inefficiency for Large Numbers:

- Counting big numbers would require repeating the base unit multiple times, which is slow and impractical.

Representing 1345 in a System That Counts Only by 5s:

1345 can be written as: 1345 = (5 × 269) + 0

So, you would represent it as “269 groups of 5” and “0 extra units.”

In a simple group-of-5 system, you’d need 269 marks or symbols, each standing for 5, which is very inefficient for large numbers.

Page 59

Figure it Out

Q1. Represent the following numbers in the Roman system.

(i) 1222

(ii) 2999

(iii) 302

(iv) 715

Ans:

Explanation:

(i) 1222

Break it down:

1000 + 200 + 20 + 2 = M + CC + XX + II

Answer: MCCXXII

(ii) 2999

Break it down:

2000 + 900 + 90 + 9 = MM + CM + XC + IX

Answer: MMCMXCIX

(iii) 302

Break it down:

300 + 2 = CCC + II

Answer: CCCII

(iv) 715

Break it down:

700 + 10 + 5 = DCC + X + V

Answer: DCCXV

Page 60

Q: Do it yourself now: LXXXVII + LXXVIII

Ans: Step 1: Write all symbols together:

L + L + X + X + X + X + X + V + V + I + I + I + I + I

Step 2: Group and simplify:

- I + I + I + I + I = V

- V + V = X

- X + X + X + X + X = L

Step 3: Now combine:

L + L = C, plus remaining X and V

Final Answer: CLXV

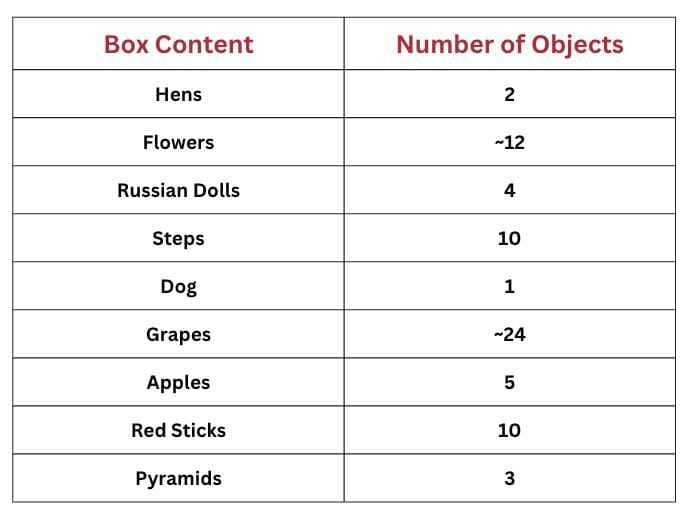

Q: How will you multiply two numbers given in Roman numerals, without converting them to Hindu numerals? Try to find the product of the following pairs of landmark numbers: V × L, L × D, V × D, VII × IX.

Ans: You cannot multiply directly in Roman numerals on an abacus. You must:

- Convert Roman → Hindu-Arabic

- Multiply using abacus

- Convert result back → Roman numeral

This method ensures accurate and efficient multiplication.

Note:

- _X = 10,000, so _XX = 20,000, and _XXV = 25,000

- Roman numerals above 3,999 use overlines to indicate multiplication by 1,000

Q: DAREDEVIL CONTEST: Multiply CCXXXI and MDCCCLII

- CCXXXI = 200 + 20 + 11 = 231

- MDCCCLII = 1000 + 700 + 50 + 2 = 1752

Multiplication in Roman numerals is impractical without conversion.

So, convert to Hindu-Arabic numerals:

231 × 1752 = 404712

Converting 404712 to Roman Numerals:

404712 = CD (400,000) + IV (4) + DCC (700) + XII (12)

So, Roman numeral: _CDIVDCCXII

(where CD means 400,000)

Page 60-70

Figure it out

Q1. A group of indigenous people in a Pacific island use different sequences of number names to count different objects. Why do you think they do this?

Ans: Different sequences help keep track of various categories of objects. This method is practical in daily life, like using one set of words for counting coconuts and another for people. It allows them to focus on context, improve accuracy, and avoid confusion.

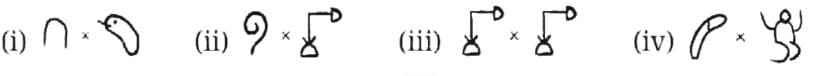

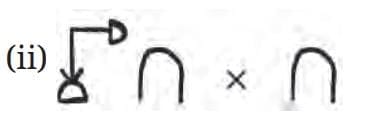

Q2. Consider the extension of the Gumulgal number system beyond 6 in the same way of counting by 2s. Come up with ways of performing the different arithmetic operations (+, –, ×, ÷)for numbers occurring in this system, without using Hindu numerals. Use this to evaluate the following:

(i) (ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-urapon) + (ukasar-ukasarukasar-urapon)

(ii) (ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-urapon) – (ukasar-ukasarukasar)

(iii) (ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-urapon) × (ukasar-ukasar)

(iv) (ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar) ÷ (ukasar-ukasar)

Ans: First, define base terms:

- urapon = 1

- ukasar = 2

So:

- ukasar-urapon = 3

- ukasar-ukasar = 4

- ukasar-ukasar-urapon = 5

- ukasar-ukasar-ukasar = 6

- ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-urapon = 7

- ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar = 8

- ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-urapon = 9

- etc.

(i) (ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-urapon) + (ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-urapon)

- First term: 4 ukasar + 1 urapon = 9

- Second term: 3 ukasar + 1 urapon = 7

Add using parts:

- 4 + 3 = 7 ukasar

- 1 + 1 = 2 urapon = 1 ukasar

Total: 7 ukasar + 1 ukasar = 8 ukasar

Answer: 8 ukasar or ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar

(ii) (ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-urapon) – (ukasar-ukasar-ukasar)

- First term = 9

- Second term = 6

Subtract by cancelling:

- Remove 3 ukasar from 4 ukasar → 1 ukasar remains

- 1 urapon stays

Answer: ukasar + urapon = ukasar-urapon

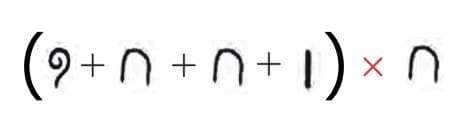

(iii) (ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-ukasar-urapon) × (ukasar-ukasar)

Multiply:

- First term = 4 ukasar + 1 urapon = 9

- Second term = 2 ukasar = 4

Use repeated addition:

- 9 × 4 = 36

- 36 = 18 ukasar

Answer: 18 ukasar

→ Write out 18 repetitions of “ukasar” if needed, or say “18 ukasar” in Gumulgal form.

(iv) (ukasar × 8) ÷ (ukasar-ukasar)

- Numerator: 8 × ukasar = 8 × 2 = 16

- Denominator: ukasar-ukasar = 4

Divide:

- 16 ÷ 4 = 4

→ 4 = ukasar-ukasar

Answer: ukasar-ukasar

Q3: Identify the features of the Hindu number system that make it efficient when compared to the Roman number system.

Ans: Features of the Hindu number system that make it efficient:

- Uses place value (units, tens, hundreds…)

- Has only 10 symbols (0–9) to write any number

- Includes zero, making calculations easier

- Easy to use for large numbers and arithmetic operations

Q4: Using the ideas discussed in this section, try refining the number system you might have made earlier.

Ans: Do it Yourself!

Hint: Tips to refine your number system

- Add symbols for higher values to reduce repetition

- Introduce place value (just like Hindu numerals)

- Define clear rules for operations (+, –, ×, ÷)

- Possibly create shortcuts or grouping patterns (like grouping by 5s or 10s) to improve speed and consistency.

Page 62

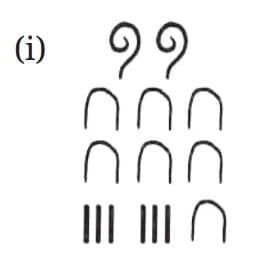

Q1: Represent the following numbers in the Egyptian system: 10458, 1023, 2660, 784, 1111, 70707.

1. 10,458

Let’s break it down:

- 1 × 10,000

- 4 × 100

- 5 × 10

- 8 × 1

Representation:

2. 1023

Let’s break it down:

- 1 × 1,000

- 0 × 100

- 2 × 10

- 3 × 1

Representation:

3. 2660

Let’s break it down:

- 2 × 1,000

- 6 × 100

- 6 × 10

- 0 × 1

Representation:

4. 784

Let’s break it down:

- 7 × 100

- 8 × 10

- 4 × 1

Representation:

5. 1111

Let’s break it down:

- 1 × 1,000

- 1 × 100

- 1 × 10

- 1 × 1

Representation:

6. 70707

Let’s break it down:

- 7 × 10,000

- 0 × 1,000

- 7 × 100

- 0 × 10

- 7 × 1

Representation:

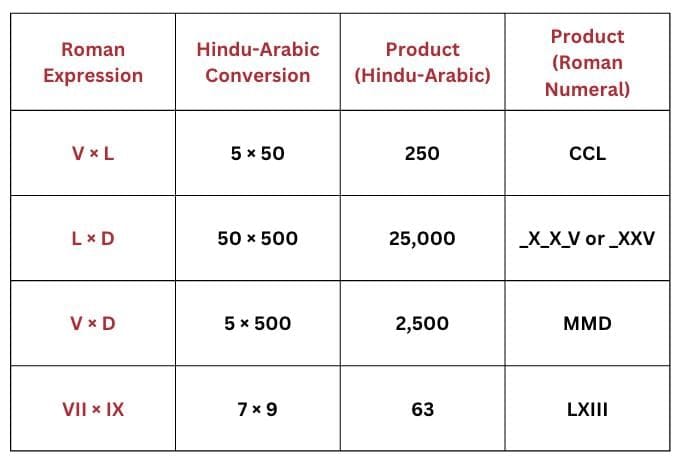

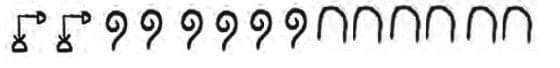

Q2: What numbers do these numerals stand for?

Ans: Using the Egyptian Number System:

- 2 × 102 = 2 × 100 = 200

- 7 × 10 = 70

- 3 × 1 = 3

Total value: 200 + 70 + 3 = 273

Ans: Using the Egyptian Number System:

- 4 × 103 = 4 × 1,000 = 5,000

- 3 × 102 = 3 × 100 = 300

- 1 × 10 = 10

- 2 × 1 = 2

Total = 4,000 + 300 + 10 + 2 = 4,312

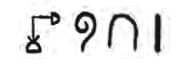

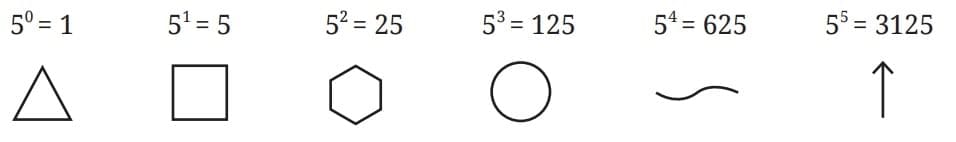

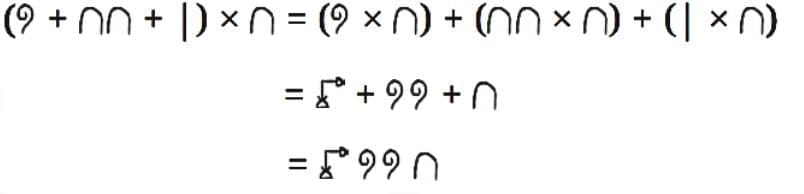

Q: Express the number 143 in this new system.

Ans: Let us start grouping, starting with the size 53 = 125, as this is the largest landmark number smaller than 143. We get—

143 = 125 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 1 + 1 + 1.

Using the standard symbols,

So the number 143 in the new system is:

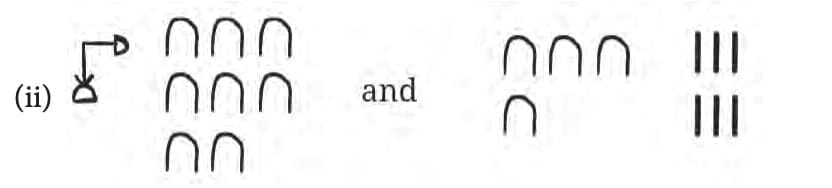

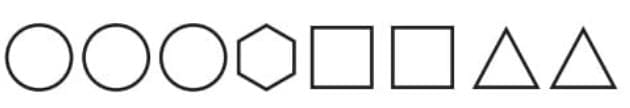

Page 63Figure it Out

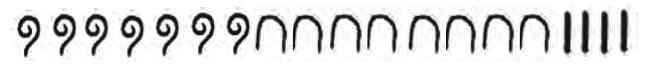

Q1. Write the following numbers in the above base-5 system using the symbols in Table 2: 15, 50, 137, 293, 651.

Ans: Representing in base-5 system

1. 15

- 25 is too big.

- Largest power: 5 (51), can use 3 times (5×3 = 15).

- 15 = 5+5+5 = 3×5

Base-5 symbols:

Base-5 symbols:

2. 50

- Largest power 52=25, fits twice.

- 5×2=50; nothing left.

Base-5 symbols:

Base-5 symbols:

3. 137

- Largest power 53=125 fits once. 137−125 = 12

- Next, 51=5 fits twice. 12−10 = 2

- Next, 50 = 1 fits twice.

- 137 = 125 + 5 + 5 + 1 + 1

Base-5 symbols:

Base-5 symbols:

4. 293

- 5⁴ = 625 is too big.

- 5³ = 125 fits twice (125 × 2 = 250). 293 − 250 = 43

- 5² = 25 fits once. 43 − 25 = 18

- 5¹ = 5 fits three times. 18 − 15 = 3

- 5⁰ = 1 fits three times.

- 293 = 125 + 125 + 25 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 1 + 1 + 1

Base-5 symbols:

Base-5 symbols:

5. 651

- 5⁴ = 625 fits once. 651 − 625 = 26

- 5² = 25 fits once. 26 − 25 = 1

- 5⁰ = 1 fits once.

- 651 = 625 + 25 + 1

Base-5 symbols:

Base-5 symbols:

Q2. Is there a number that cannot be represented in our base-5 system above? Why or why not?

Ans: No, every whole number can be represented in base-5.

This is because base-5 is a positional numeral system, and like base-10, it can represent any non-negative integer using combinations of digits 0–4.

Q3. Compute the landmark numbers of a base-7 system. In general, what are the landmark numbers of a base-n system? The landmark numbers of a base-n number system are the powers of n starting from n0 = 1, n, n2, n3, …

Ans: Landmark numbers of base-7:

- 7⁰ = 1

- 7¹ = 7

- 7² = 49

- 7³ = 343

- 7⁴ = 2401

In general, the landmark numbers of a base-n system are:

1, n, n², n³, n⁴, …

That is, powers of n, starting from n0 = 1.

Page 65

Figure it Out

Q1. Add the following Egyptian numerals:

Ans: Try it yourself!

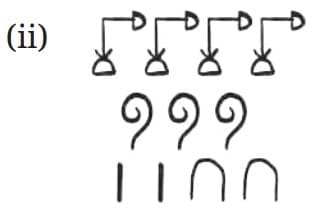

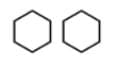

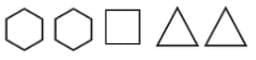

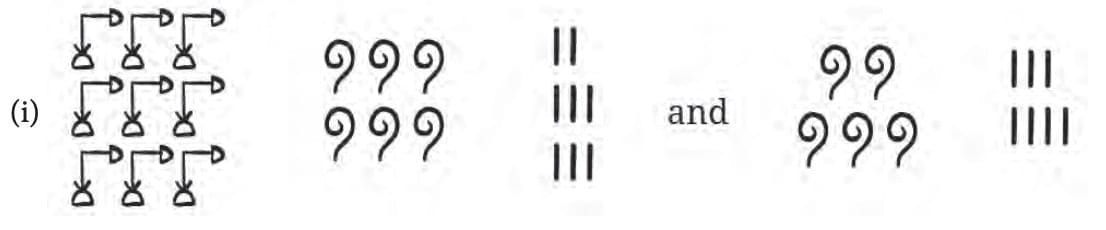

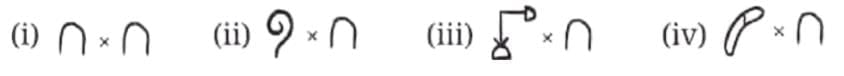

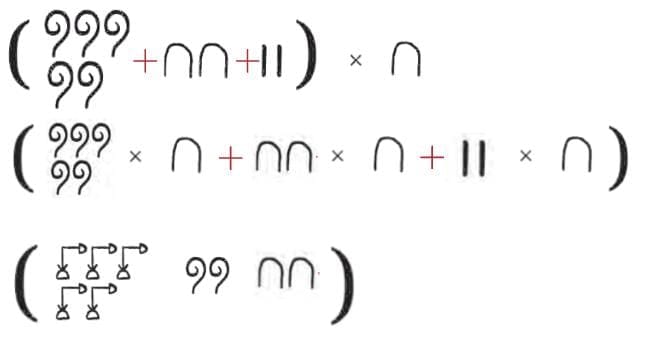

Q2. Add the following numerals that are in the base-5 system that we created:

Remember that in this system, 5 times a landmark number gives the next one!

Ans: Let’s convert this to numerals

First numeral (left side)

This is: 1 circle, 2 hexagons, 1 square, 2 triangles

Value:

- 1 × 125 = 125

- 2 × 25 = 50

- 1 × 5 = 5

- 2 × 1 = 2

Sum: 125 + 50 + 5 + 2 = 182

Second numeral (right side):

Value:

- 3 × 125 = 375

- 1 × 25 = 25

- 2 × 5 = 10

- 2 × 1 = 2

Sum: 375 + 25 + 10 + 2 = 412

Page 66

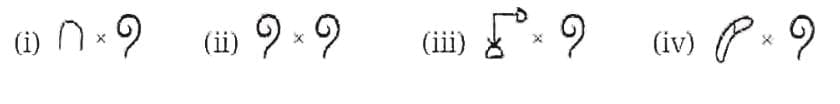

Q: How to multiply two numbers in Egyptian numerals?

Let us first consider the product of two landmark numbers.

1. What is any landmark number multiplied by (that is 10)? Find the following products—

(i) 10 × 10 = 100

100 =

(ii) 100 × 10= 1,000

1,000 =

(iii) 1,000 × 10 = 10,000

10,000 =

(iv) 10,000 × 10 = 100,000

100,000 =

Each landmark number is a power of 10 and so multiplying it with10 increases the power by 1, which is the next landmark number.

2. What is any landmark number multiplied by (102)? Find the following products—

(i) 10 × 100 = 1,000

1,000 =

(ii) 100 × 100 = 10,000

10,000 =

(iii) 1,000 × 100 = 100,000

100,000 =

(iv) 10,000 × 100 = 1,000,000

1,000,000 =

Each landmark number represents a power of 10, so multiplying it by 102 increases the power by 2, resulting in the landmark number that is two steps higher.

Page 67

Q: Find the following products—

Here are the computations for each part:

(i) 10 × 100,000 = 1,000,000

1,000,000 =

(ii) 100 × 1,000 = 100,000

100,000 =

(iii) 1,000 × 1,000 = 1,000,000

1,000,000 =

(iv) 10,000 × 1,000,000 = 10,000,000,000 = 1010

Thus, the product of any two landmark numbers is another landmark number!

Q: Does this property hold true in the base-5 system that we created? Does this hold for any number system with a base?

Ans: In any place-value system, each “landmark number” is just a power of the base:

- In base-10 → 10, 100, 1,000 are powers of 10

- In base-5 → 5, 25, 125 are powers of 5

When you multiply a landmark by the base, it just moves to the next bigger landmark.

Q: What can we conclude about the product of a number and (10), in the Egyptian system?

(i)

Ans:

As these are numbers, the distributive law holds. So,

(ii)

Ans: We can expandas

Applying the distributive property

Now find the following products—

Ans: Applying the distributive property

Page 69-70

Figure it Out

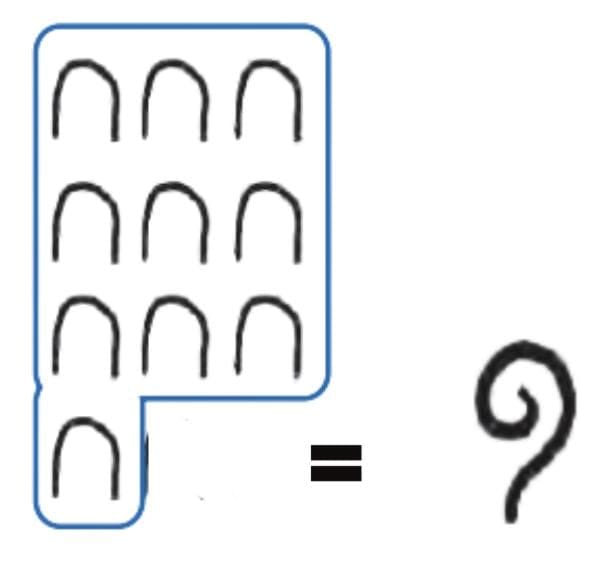

Q1. Can there be a number whose representation in Egyptian numerals has one of the symbols occurring 10 or more times? Why not?

Ans: No, you cannot have one symbol appear 10 or more times in a standard Egyptian numeral.

Reason:

Egyptian numerals use a form of additive system—each symbol represents a power of ten (1, 10, 100, 1,000, etc.). To write a number, you repeat the symbol as many times as needed (up to 9). But as soon as you reach 10 of a symbol, you replace it with a single symbol of the next higher value.

Example:

- Nine arches (10s) = 90

Ten arches (10s) would be written as one spiral (100), not 10 arches.

Ten arches (10s) would be written as one spiral (100), not 10 arches.

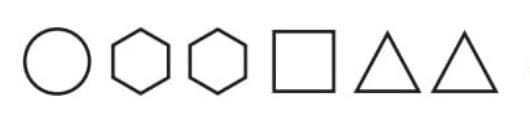

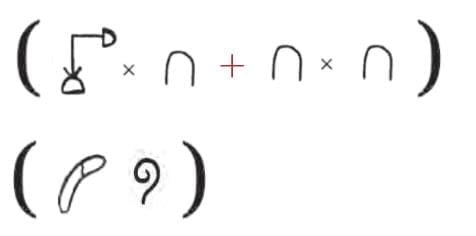

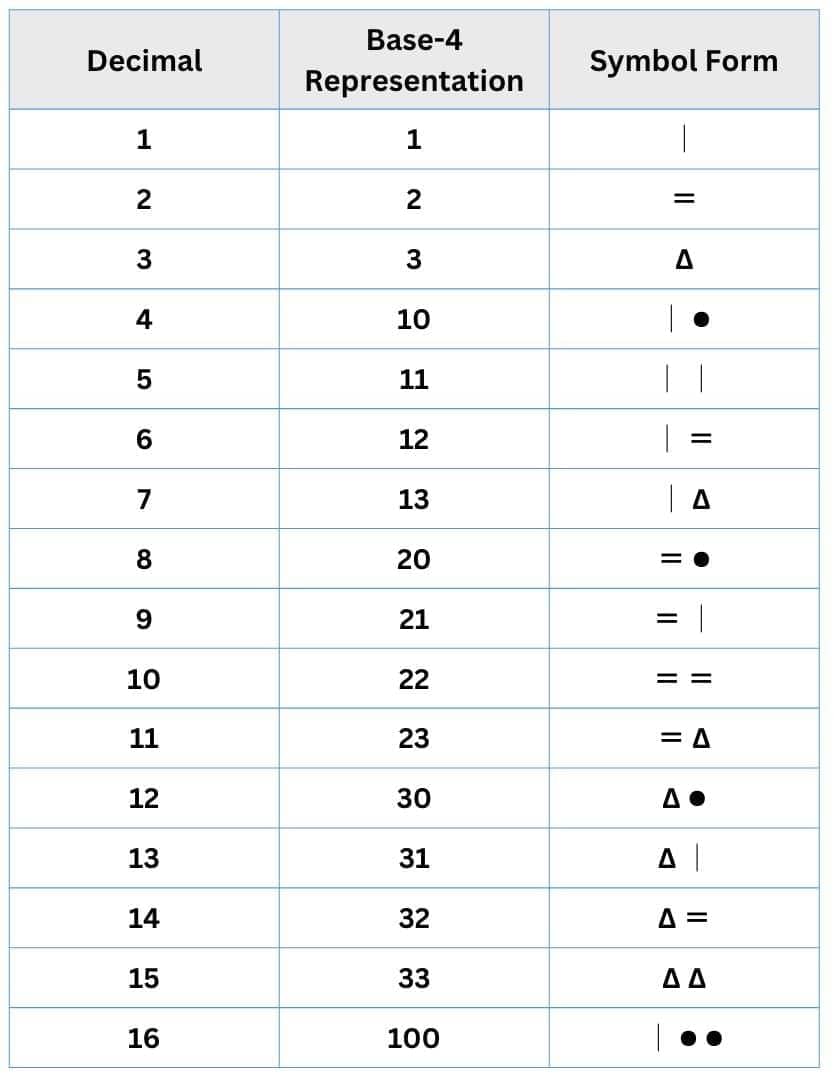

Q2. Create your own number system of base 4, and represent numbers from 1 to 16.

Ans: Try it yourself!

Hint: Let’s assign easy-to-draw symbols to each digit (in place of usual 0, 1, 2, 3):

- 0: • (dot)

- 1: | (vertical line)

- 2: = (double line)

- 3: ∆ (triangle)

Base-4 has places: 4¹, 4⁰, etc.

Q3. Give a simple rule to multiply a given number by 5 in the base-5 system that we created.

Ans: Simple Rule: To multiply a number by 5 in base-5, add a zero to the right of the number (just as multiplying by 10 in decimal adds a zero).

Example:

- In base-5, 213₅ × 5 = 2130₅.

- In symbols (using previous base-5 system):Suppose ■ stands for the base-5 digit “1”, then this rule means you just add a new place with a 0 (the lowest symbol or blank).

Why?

Because each shift to the left increases the place value by one power of 5, so the new number is five times as large.

Page 73Figure it Out

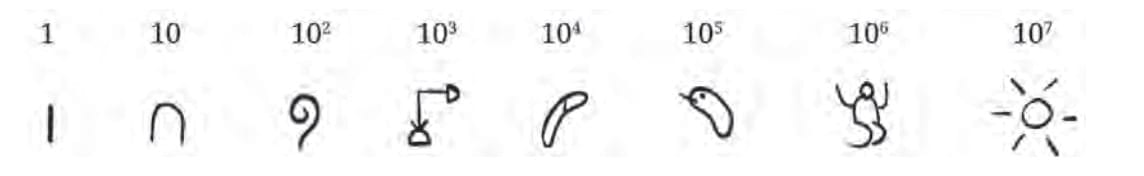

Q1. Represent the following numbers in the Mesopotamian system using—

(i) 63

(ii) 132

(iii) 200

(iv) 60

(v) 3605

Ans:

(i) 63

(ii) 132

(iii) 200

(iv) 60

(v) 3605

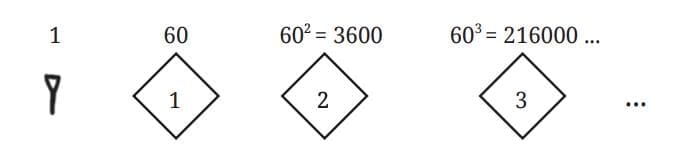

Q: Look at the representation of 60. What will be the representation for 3,600?

Ans:The representation for 3,600 is a single mark or symbol in the “2” diamond.

Page 76

Q: Represent the following numbers using the Mayan system:

(i) 77

(ii) 100

(iii) 361

(iv) 721

Ans: Try it Yourself!

Page 78

Q: Where does the Hindu/Indian number system figure in the evolution of ideas of number representation? What are its landmark numbers? And does it use a place value system?

Ans: The Hindu/Indian number system plays a crucial role in the evolution of number representation. It introduced two major innovations:

- The concept of zero as a digit, and

- A place value system based on base-10.

These ideas greatly simplified writing and calculating large numbers and influenced the development of modern numerals used worldwide today (often called Hindu-Arabic numerals).

Landmark numbers in this system are powers of 10, such as:

- 1 (10⁰)

- 10 (10¹)

- 100 (10²)

- 1,000 (10³), and so on.

Yes, the Hindu number system uses a place value system, meaning the position of a digit determines its value based on powers of 10. For example, in the number 345, the digit 3 represents 300 (3 × 100), 4 represents 40 (4 × 10), and 5 represents 5 (5 × 1).

This system laid the foundation for modern arithmetic and digital computation.

Page 80Figure it Out

Q1. Why do you think the Chinese alternated between the Zong and Heng symbols? If only the Zong symbols were to be used, how would 41 be represented? Could this numeral be interpreted in any other way if there is no significant space between two successive positions?

Ans: Using Zong and Heng symbols:

- The Chinese number system used Zong (vertical) and Heng (horizontal) symbols to show place value clearly.

- They alternated the direction of the symbols at each place (units, tens, hundreds, etc.) to avoid confusion when reading the number.

- This made it easier to know which digit belonged to which place even when spaces were small or missing.In Chinese system: 41 = 4 tens and 1 unit.

Using only Zong symbols, it would be written as:

(Zong for 4) followed by (Zong for 1) → looks like: IIII I

Without alternating the symbol direction or keeping proper spacing, IIIII could be misread as 5 (i.e., 1 five) instead of 41.

The lack of direction or spacing removes the clue that one part is “tens” and the other is “units”.

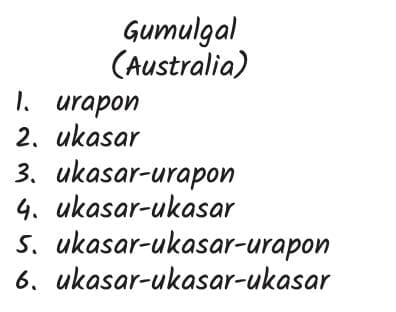

Q2. Form a base-2 place value system using ‘ukasar’ and ‘urapon’ as the digits. Compare this system with that of the Gumulgal’s.

Ans: To form a base-2 place value system using ‘ukasar’ and ‘urapon’, we assign:

• ‘ukasar’ = 0

• ‘urapon’ = 1

This system works just like the binary number system, where each position from right to left represents increasing powers of 2. For example:

• The first place is 2⁰ = 1

• The next is 2¹ = 2

• Then 2² = 4 and so on.

So, we can represent numbers like this

A group of indigenous people in Australia called the Gumulgal had the following words for their numbers.

In the Gumulgal System, we can name every number, but in the binary system, only the numbers shown in the table have names.

Q3. Where in your daily lives, and in which professions, do the Hindu numerals, and 0, play an important role? How might our lives have been different if our number system and 0 hadn’t been invented or conceived of?

Ans: Hindu numerals Usage

- Hindu numerals and the digit zero are used in everyday life, such as telling time, counting and managing money, reading prices, doing mathematics in school, writing phone numbers, etc.

- Professions like banking, teaching, engineering, and science rely heavily on this number system.

- Zero is especially important because it helps in representing place value and making large numbers easy to write and understand

Without zero and the Hindu numeral system:

- Basic calculations would be very difficult.

- Trading and writing dates would be challenging

- Technology like computers and calculators wouldn’t exist

- Progress in all fields would be much slower

Q4. The ancient Indians likely used base 10 for the Hindu number system because humans have 10 fingers, and so we can use our fingers to count. But what if we had only 8 fingers? How would we be writing numbers then? What would the Hindu numerals look like if we were using base 8 instead? Base 5? Try writing the base-10 Hindu numeral 25 as base-8 and base-5 Hindu numerals, respectively. Can you write it in base-2?

Ans: If we had only 8 fingers, we might have used base-8. Similarly, with 5 fingers, we could have used base-5.

Let’s convert the base-10 number 25 into different bases:

1. Base-8:

25 ÷ 8 = 3 remainder 1

3 ÷ 8 = 0 remainder 3

So, 25 in base-8 = 31

2. Base-5:

25 ÷ 5 = 5 remainder 0

5 ÷ 5 = 1 remainder 0

1 ÷ 5 = 0 remainder 1

So, 25 in base-5 = 100

3. Base-2:

25 ÷ 2 = 12 remainder 1

12 ÷ 2 = 6 remainder 0

6 ÷ 2 = 3 remainder 0

3 ÷ 2 = 1 remainder 1

1 ÷ 2 = 0 remainder 1

So, 25 in base-2 = 11001

In base-8 or base-5 systems, the Hindu numerals would have included only the digits needed (0 to 7 for base-8, and 0 to 4 for base-5).