Exercise 7.1

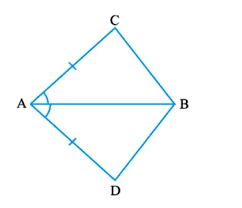

Q1. In quadrilateral ACBD, AC = AD and AB bisects ∠ A. Show that ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ ABD. What can you say about BC and BD?

Ans: It is given that AC and AD are equal i.e. AC = AD and the line segment AB bisects ∠A.

We will have to now prove that the two triangles ABC and ABD are similar i.e. ΔABC ≅ ΔABD

Proof:

Consider the triangles ΔABC and ΔABD,

(i) AC = AD (It is given in the question)

(ii) AB = AB (Common

(iii) ∠CAB = ∠DAB (Since AB is the bisector of angle A)

So, by SAS congruency criterion, ΔABC ≅ ΔABD.

For the 2nd part of the question, BC and BD are of equal lengths by the rule of C.P.C.T.

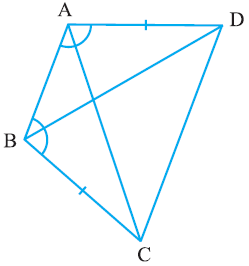

Q2. ABCD is a quadrilateral in which AD = BC and ∠ DAB = ∠ CBA. Prove that

(i) ∆ ABD ≅ ∆ BAC

(ii) BD = AC

(iii) ∠ ABD = ∠ BAC

Ans: The given parameters from the questions are ∠DAB = ∠CBA and AD = BC.

(i) ΔABD and ΔBAC are similar by SAS congruency as

AB = BA (It is the common arm)

∠DAB = ∠CBA and AD = BC (These are given in the question)

So, triangles ABD and BAC are similar i.e. ΔABD ≅ ΔBAC. (Hence proved).

(ii) It is now known that ΔABD ≅ ΔBAC so,

BD = AC (by the rule of CPCT).

(iii) Since ΔABD ≅ ΔBAC so,

Angles ∠ABD = ∠BAC (by the rule of CPCT).

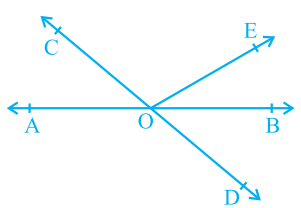

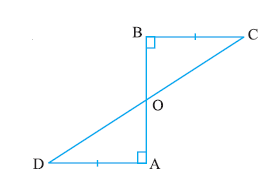

Q3. AD and BC are equal perpendiculars to a line segment AB. Show that CD bisects AB.

Ans: It is given that AD and BC are two equal perpendiculars to AB.

We will have to prove that CD is the bisector of AB

Now,

Triangles ΔAOD and ΔBOC are similar by AAS congruency since:

(i) ∠A = ∠B (They are perpendiculars)

(ii) AD = BC (As given in the question)

(iii) ∠AOD = ∠BOC (They are vertically opposite angles)

∴ ΔAOD ≅ ΔBOC.

So, AO = OB (by the rule of CPCT).

Thus, CD bisects AB (Hence proved).

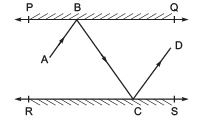

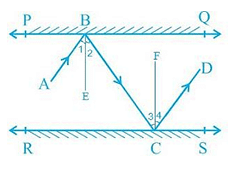

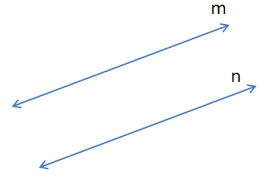

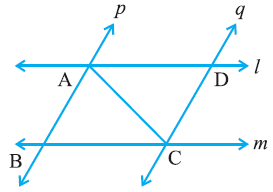

Q4. l and m are two parallel lines intersected by another pair of parallel lines p and q. Show that ∆ ABC ≅ ∆ CDA.

Ans: It is given that p || q and l || m

To prove:

Triangles ABC and CDA are similar i.e. ΔABC ≅ ΔCDA

Proof:

Consider the ΔABC and ΔCDA,

(i) ∠BCA = ∠DAC and ∠BAC = ∠DCA Since they are alternate interior angles

(ii) AC = CA as it is the common arm

So, by ASA congruency criterion, ΔABC ≅ ΔCDA.

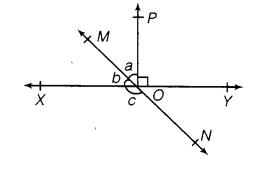

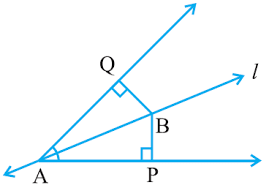

Q5. Line l is the bisector of an angle ∠ A and B is any point on l. BP and BQ are perpendiculars from B to the arms of ∠ A. Show that:

(i) ∆ APB ≅ ∆ AQB

(ii) BP = BQ or B is equidistant from the arms of ∠ A.

Ans: It is given that the line “l” is the bisector of angle ∠A and the line segments BP and BQ are perpendiculars drawn from l.

(i) ΔAPB and ΔAQB are similar by AAS congruency because:

∠P = ∠Q (They are the two right angles)

AB = AB (It is the common arm)

∠BAP = ∠BAQ (As line l is the bisector of angle A)

So, ΔAPB ≅ ΔAQB.

(ii) By the rule of CPCT, BP = BQ. So, it can be said the point B is equidistant from the arms of ∠A.

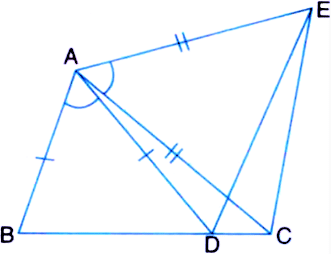

Q6. In the following figure, AC = AE, AB = AD and ∠ BAD = ∠ EAC. Show that BC = DE.

Ans: It is given in the question that AB = AD, AC = AE, and ∠BAD = ∠EAC

To prove:

The line segment BC and DE are similar i.e. BC = DE

Proof:

We know that ∠BAD = ∠EAC

Now, by adding ∠DAC on both sides we get,

∠BAD + ∠DAC = ∠EAC +∠DAC

This implies, ∠BAC = ∠EAD

Now, ΔABC and ΔADE are similar by SAS congruency since:

(i) AC = AE (As given in the question)

(ii) ∠BAC = ∠EAD

(iii) AB = AD (It is also given in the question)

∴ Triangles ABC and ADE are similar i.e. ΔABC ≅ ΔADE.

So, by the rule of CPCT, it can be said that BC = DE.

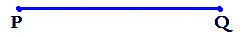

Q7. AB is a line segment and P is its mid-point. D and E are points on the same side of AB such that ∠ BAD = ∠ ABE and ∠ EPA = ∠ DPB. Show that

(i) ∆ DAP ≅ ∆ EBP

(ii) AD = BE

Ans: In the question, it is given that P is the mid-point of line segment AB. Also, ∠BAD = ∠ABE and ∠EPA = ∠DPB

(i) It is given that ∠EPA = ∠DPB

Now, add ∠DPE on both sides,

∠EPA +∠DPE = ∠DPB+∠DPE

This implies that angles DPA and EPB are equal i.e. ∠DPA = ∠EPB

Now, consider the triangles DAP and EBP.

∠DPA = ∠EPB

AP = BP (Since P is the mid-point of the line segment AB)

∠BAD = ∠ABE (As given in the question)

So, by ASA congruency, ΔDAP ≅ ΔEBP.

(ii) By the rule of CPCT, AD = BE.

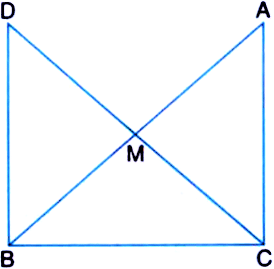

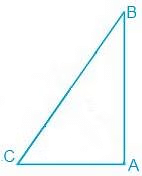

Q8. In right triangle ABC, right angled at C, M is the mid-point of hypotenuse AB. C is joined to M and produced to a point D such that DM = CM. Point D is joined to point B. Show that:

(i) ∆ AMC ≅ ∆ BMD

(ii) ∠ DBC is a right angle.

(iii) ∆ DBC ≅ ∆ ACB

(iv) CM = ½ AB

Ans: It is given that M is the mid-point of the line segment AB, ∠C = 90°, and DM = CM

(i) Consider the triangles ΔAMC and ΔBMD:

AM = BM (Since M is the mid-point)

CM = DM (Given in the question)

∠CMA = ∠DMB (They are vertically opposite angles)

So, by SAS congruency criterion, ΔAMC ≅ ΔBMD.

(ii) ∠ACM = ∠BDM (by CPCT)

∴ AC || BD as alternate interior angles are equal.

Now, ∠ACB +∠DBC = 180° (Since they are co-interiors angles)

⇒ 90° +∠B = 180°

∴ ∠DBC = 90°

(iii) In ΔDBC and ΔACB,

BC = CB (Common side)

∠ACB = ∠DBC (They are right angles)

DB = AC (by CPCT)

So, ΔDBC ≅ ΔACB by SAS congruency.

(iv) DC = AB (Since ΔDBC ≅ ΔACB)

⇒ DM = CM = AM = BM (Since M the is mid-point)

So, DM + CM = BM+AM

Hence, CM + CM = AB

⇒ CM = (½) AB

Exercise 7.2

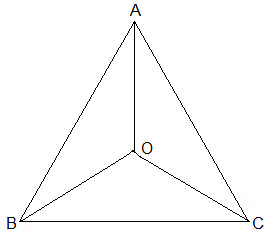

Q1. In an isosceles triangle ABC, with AB = AC, the bisectors of ∠ B and ∠ C intersect each other at O. Join A to O. Show that:

(i) OB = OC

(ii) AO bisects ∠ A

Ans:

Given:

AB = AC and

the bisectors of ∠B and ∠C intersect each other at O

(i) Since ABC is an isosceles with AB = AC,

∠B = ∠C

½ ∠B = ½ ∠C

⇒ ∠OBC = ∠OCB (Angle bisectors)

∴ OB = OC (Side opposite to the equal angles are equal.)

(ii) In ΔAOB and ΔAOC,

AB = AC (Given in the question)

AO = AO (Common arm)

OB = OC (As Proved Already)

So, ΔAOB ≅ ΔAOC by SSS congruence condition.

BAO = CAO (by CPCT)

Thus, AO bisects ∠A.

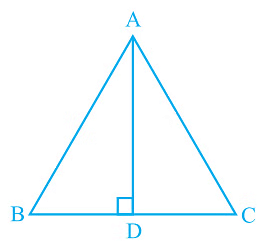

Q2. In ΔABC, AD is the perpendicular bisector of BC (see Fig.). Show that ΔABC is an isosceles triangle in which AB = AC.

Ans: It is given that AD is the perpendicular bisector of BC

To prove:

AB = AC

Proof:

In ΔADB and ΔADC,

AD = AD (It is the Common arm)

∠ADB = ∠ADC

BD = CD (Since AD is the perpendicular bisector)

So, ΔADB ≅ ΔADC by SAS congruency criterion.

Thus,

AB = AC (by CPCT)

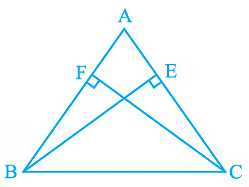

Q3. ABC is an isosceles triangle in which altitudes BE and CF are drawn to equal sides AC and AB respectively (see Fig.). Show that these altitudes are equal.

Ans:

Given:

(i) BE and CF are altitudes.

(ii) AC = AB

To prove:

BE = CF

Proof:

Triangles ΔAEB and ΔAFC are similar by AAS congruency since

∠A = ∠A (It is the common arm)

∠AEB = ∠AFC (They are right angles)

AB = AC (Given in the question)

∴ ΔAEB ≅ ΔAFC and so, BE = CF (by CPCT).

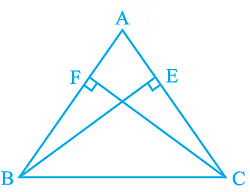

Q4. ABC is a triangle in which altitudes BE and CF to sides AC and AB are equal (see Fig). Show that

(i) ∆ ABE ≅ ∆ ACF

(ii) AB = AC, i.e., ABC is an isosceles triangle.

Ans: It is given that BE = CF

(i) In ΔABE and ΔACF,

∠A = ∠A (It is the common angle)

∠AEB = ∠AFC (They are right angles)

BE = CF (Given in the question)

∴ ΔABE ≅ ΔACF by AAS congruency condition.

(ii) AB = AC by CPCT and so, ABC is an isosceles triangle.

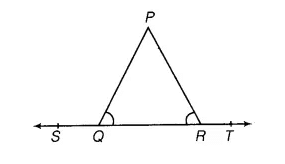

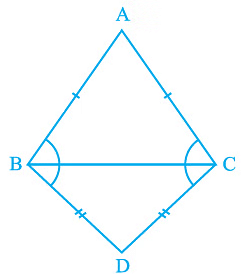

Q5. ABC and DBC are two isosceles triangles on the same base BC (see Fig). Show that ∠ ABD = ∠ ACD.

Ans: In the question, it is given that ABC and DBC are two isosceles triangles.

We will have to show that ∠ABD = ∠ACD

Proof:

Triangles ΔABD and ΔACD are similar by SSS congruency since

AD = AD (It is the common arm)

AB = AC (Since ABC is an isosceles triangle)

BD = CD (Since BCD is an isosceles triangle)

So, ΔABD ≅ ΔACD.

∴ ∠ABD = ∠ACD by CPCT.

Q6. ∆ABC is an isosceles triangle in which AB = AC. Side BA is produced to D such that AD = AB (see Fig). Show that ∠ BCD is a right angle.

Ans: It is given that AB = AC and AD = AB

We will have to now prove ∠BCD is a right angle.

Proof:

Consider ΔABC,

AB = AC (It is given in the question)

Also, ∠ACB = ∠ABC (They are angles opposite to the equal sides and so, they are equal)

Now, consider ΔACD,

AD = AB

Also, ∠ADC = ∠ACD (They are angles opposite to the equal sides and so, they are equal)

Now,

In ΔABC,

∠CAB + ∠ACB + ∠ABC = 180°

So, ∠CAB + 2∠ACB = 180°

⇒ ∠CAB = 180° – 2∠ACB — (i)

Similarly, in ΔADC,

∠CAD = 180° – 2∠ACD — (ii)

also,

∠CAB + ∠CAD = 180° (BD is a straight line.)

Adding (i) and (ii) we get,

∠CAB + ∠CAD = 180° – 2∠ACB+180° – 2∠ACD

⇒ 180° = 360° – 2∠ACB-2∠ACD

⇒ 2(∠ACB+∠ACD) = 180°

⇒ ∠BCD = 90°

Q7. ABC is a right angled triangle in which ∠ A = 90° and AB = AC. Find ∠ B and ∠ C.

Ans:

In the question, it is given that

∠A = 90° and AB = AC

AB = AC

⇒ ∠B = ∠C (They are angles opposite to the equal sides and so, they are equal)

Now,

∠A+∠B+∠C = 180° (Since the sum of the interior angles of the triangle)

∴ 90° + 2∠B = 180°

⇒ 2∠B = 90°

⇒ ∠B = 45°

So, ∠B = ∠C = 45°

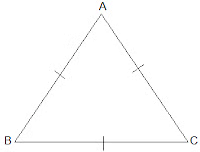

Q8. Show that the angles of an equilateral triangle are 60° each.

Ans: Let ABC be an equilateral triangle as shown below:

Here, BC = AC = AB (Since the length of all sides is same)⇒ ∠A = ∠B =∠C (Sides opposite to the equal angles are equal.)Also, we know that

∠A+∠B+∠C = 180°

⇒ 3∠A = 180°

⇒ ∠A = 60°

∴ ∠A = ∠B = ∠C = 60°

So, the angles of an equilateral triangle are always 60° eac

Exercise 7.3

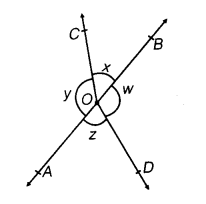

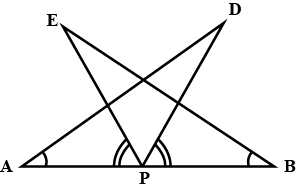

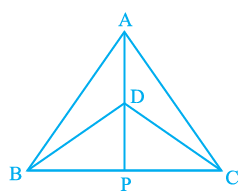

Q1. ∆ ABC and ∆ DBC are two isosceles triangles on the same base BC and vertices A and D are on the same side of BC (see Fig). If AD is extended to intersect BC at P, show that

(i) ΔABD ≅ ΔACD

(ii) ΔABP ≅ ΔACP

(iii) AP bisects ∠A as well as ∠D.

(iv) AP is the perpendicular bisector of BC.

Ans: In the above question, it is given that ΔABC and ΔDBC are two isosceles triangles.

(i) ΔABD and ΔACD are similar by SSS congruency because:

AD = AD (It is the common arm)

AB = AC (Since ΔABC is isosceles)

BD = CD (Since ΔDBC is isosceles)

∴ ΔABD ≅ ΔACD.

(ii) ΔABP and ΔACP are similar as:

AP = AP (It is the common side)

∠PAB = ∠PAC (by CPCT since ΔABD ≅ ΔACD)

AB = AC (Since ΔABC is isosceles)

So, ΔABP ≅ ΔACP by SAS congruency condition.

(iii) ∠PAB = ∠PAC by CPCT as ΔABD ≅ ΔACD.

AP bisects ∠A. — (i)

Also, ΔBPD and ΔCPD are similar by SSS congruency as

PD = PD (It is the common side)

BD = CD (Since ΔDBC is isosceles.)

BP = CP (by CPCT as ΔABP ≅ ΔACP)

So, ΔBPD ≅ ΔCPD.

Thus, ∠BDP = ∠CDP by CPCT. — (ii)

Now by comparing (i) and (ii) it can be said that AP bisects ∠A as well as ∠D.

(iv) ∠BPD = ∠CPD (by CPCT as ΔBPD ΔCPD)

and BP = CP — (i)

also,

∠BPD +∠CPD = 180° (Since BC is a straight line.)

⇒ 2∠BPD = 180°

⇒ ∠BPD = 90° —(ii)

Now, from equations (i) and (ii), it can be said that

AP is the perpendicular bisector of BC.

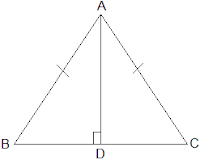

Q2. AD is an altitude of an isosceles triangle ABC in which AB = AC. Show that

(i) AD bisects BC

(ii) AD bisects ∠ A.

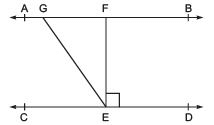

Ans: It is given that AD is an altitude and AB = AC. The diagram is as follows:

(i) In ΔABD and ΔACD,

∠ADB = ∠ADC = 90°

AB = AC (It is given in the question)

AD = AD (Common arm)

∴ ΔABD ≅ ΔACD by RHS congruence condition.

Now, by the rule of CPCT,

BD = CD.

So, AD bisects BC

(ii) Again, by the rule of CPCT, ∠BAD = ∠CAD

Hence, AD bisects ∠A.

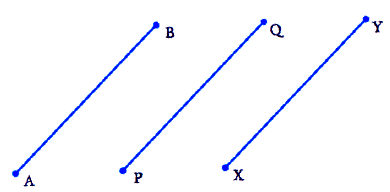

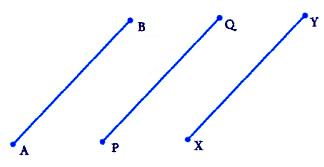

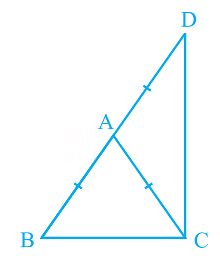

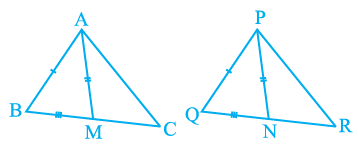

Q3. Two sides AB and BC and median AM of one triangle ABC are respectively equal to sides PQ and QR and median PN of ΔPQR (see Fig). Show that:

(i) ΔABM ≅ ΔPQN

(ii) ΔABC ≅ ΔPQR

Ans: Given parameters are:

AB = PQ,

BC = QR and

AM = PN

(i) ½ BC = BM and ½ QR = QN (Since AM and PN are medians)

Also, BC = QR

So, ½ BC = ½ QR

⇒ BM = QN

In ΔABM and ΔPQN,

AM = PN and AB = PQ (As given in the question)

BM = QN (Already proved)

∴ ΔABM ≅ ΔPQN by SSS congruency.

(ii) In ΔABC and ΔPQR,

AB = PQ and BC = QR (As given in the question)

∠ABC = ∠PQR (by CPCT)

So, ΔABC ≅ ΔPQR by SAS congruency.

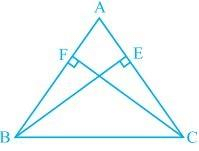

Q4. BE and CF are two equal altitudes of a triangle ABC. Using RHS congruence rule, prove that the triangle ABC is isosceles.

Ans: It is known that BE and CF are two equal altitudes.

Now, in ΔBEC and ΔCFB,

∠BEC = ∠CFB = 90° (Same Altitudes)

BC = CB (Common side)

BE = CF (Common side)

So, ΔBEC ≅ ΔCFB by RHS congruence criterion.

Also, ∠C = ∠B (by CPCT)

Therefore, AB = AC as sides opposite to the equal angles is always equal.

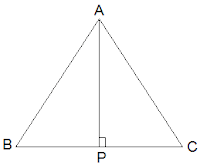

Q5. ABC is an isosceles triangle with AB = AC. Draw AP ⊥ BC to show that ∠ B = ∠ C.

Ans:

In the question, it is given that AB = AC

Now, ΔABP and ΔACP are similar by RHS congruency as

∠APB = ∠APC = 90° (AP is altitude)

AB = AC (Given in the question)

AP = AP (Common side)

So, ΔABP ≅ ΔACP.

∴ ∠B = ∠C (by CPCT)